Indians or Native Americans?

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Americas, their descendants, and many ethnic groups who identify with those peoples. They are often also referred to as Native Americans, First Nations and by Christopher Columbus' historical mistake "American Indians" or "AmerIndians".

According to the still debated New World migration model, a migration of humans from Eurasia to the Americas took place via Beringia, a land bridge which formerly connected the two continents across what is now the Bering Strait. The minimum time depth by which this migration had taken place is confirmed at c. 12,000 years ago, with the upper bound (or earliest period) remaining a matter of some unresolved contention.[1] These earlyPaleoamericans soon spread throughout the Americas, diversifying into many hundreds of culturally distinct nations and tribes.[2] According to the oral histories of many of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, they have been living there since their genesis, described by a wide range of traditional creation accounts.

Application of the term "Indian" originated with Christopher Columbus, who thought that he had arrived in the East Indies, while seeking India. This has served to imagine a kind of racial or cultural unity for the aboriginal peoples of the Americas. Once created, the unified "Indian" was codified in law, religion, and politics. The unitary idea of "Indians" was not originally shared by indigenous peoples, but many now embrace the identity.

While some indigenous peoples of the Americas were historically hunter-gatherers, many practiced aquacultureand agriculture. The impact of their agricultural endowment to the world is a testament to their time and work in reshaping, taming, and cultivating the flora indigenous to the Americas.[3] Some societies depended heavily on agriculture while others practiced a mix of farming, hunting, and gathering. In some regions the indigenous peoples created monumental architecture, large-scale organized cities, chiefdoms, states, and massive empires.

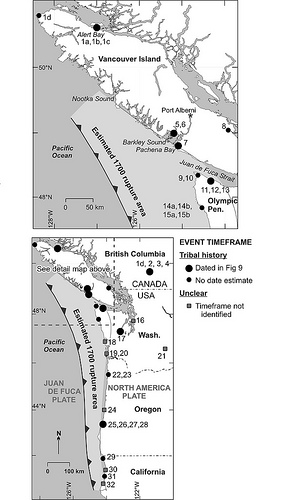

Although scientific recognition of the earthquake hazards presented by the Cascadia subduction zone (CSZ) is relatively recent, Native Americans have lived on the Cascadia coast for thousands of years, transferring knowledge from generation to generation through storytelling (Ludwin et al., 2005)

The 1980s was a decade of discovery of evidence for great earthquakes in the Cascadia Region. Tom Heaton and Hiroo Kanamori published a paper asserting the Cascadia Subduction Zone was indeed actively deforming and is likely to produce great Earthquakes. Heaton followed this paper up with a paper about PNW Native American stories that inferred their people were impacted by tsunamis in the not too distant past. In the 1990s, PNSN Research Scientist Ruth Ludwin began collecting and organizing other Native American stories and traditions that seem to be related to earthquakes and their effects on the people of Cascadia before westerners arrived.

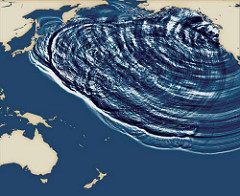

Brian Atwater, David Yamaguchi and others produced detailed evidence of abrupt land level changes and tsunami inundation along the coast of Washington state in the winter of 1699-1700. Further work in the 1980s and 1990s refined our understanding of the great earthquake that occurred on January 26, 1700 at about 9 PM PST. The amazing specificity of date and time came through collaborations with Japanese scientists and historians who helped identify the Cascadia Subduction Zone as the source of a deadly “orphan tsunami” that flooded areas on the coast of Japan the following day. Over the past 3,500 years these great earthquakes (~M9) have reoccurred 7 times with a average interval of 550 years though 4 of the events reoccurred between 200 and 400 years after the previous great quake. This research renewed interest in understanding how these events may have impacted the many thousands of Native Americans living here.

Pacific Northwest Indian tales and legends related to the 1700 megathrust earthquake and found a set of related stories that, taken together, indicate that strong shaking was felt over a wide area and accompanied by severe coastal flooding. Native traditions tell of shaking and flooding along the Cascadia coast and estimate the date of the last earthquake by using stories that count the number of generations since its occurrence. These stories are common among the native people in the Pacific Northwest. For further reading about dating the 1700 Cascadia earthquake and Native American stories, please go to Dating the 1700 Cascadia Earthquake and Native Lore Tells the Tale.

First Nations Peoples, the original inhabitants of what is now the United States, are diverse and growing populations. There are approximately 5.2 million First Nations Peoples within the boundaries of the United States, accounting for 1.7% of the general population (Norris, Vines, & Hoeffel, 2012). First Nations people tend to be younger, poorer, and less educated than others in the United States. The contemporary issues faced by these peoples are intimately intertwined with the history of colonization and current federal policies that perpetuate dependency and undermine self-determination. Social workers must overcome the negative history of the profession with First Nations Peoples, in particular social work involvement in extensive child removals and coercive sterilization of Indigenous women. Social workers have the power and ability to make important differences in enhancing the social and health status of First Nations Peoples, but this must begin with an awareness of their own attitudes and beliefs, as well as an awareness of how social workers have contributed to, rather than worked to alleviate, the problems of First Nations Peoples.

Keywords: American Indians, First Nations Peoples, Indian Child Welfare Act, Indigenous, Native Americans, sovereignty.

First Nations Peoples, also known as Native Americans, American Indians, and Indigenous Peoples, are the original inhabitants of what is now the United States. Indeed, Indigenous people are found throughout the world and some of their territories straddle international borders. For example, the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation is partly within the United States and partly within Canada. This article focuses on First Nations Peoples within the United States, but it is important to keep in mind that Indigenous Peoples transcend national divisions.

Indians or Native Americans?

Our Native American inhabitants were incorrectly called Indians by early European explorers who mistakenly believed that they had reached India. Unfortunately, the mistake persists to this day, and many people still refer to all Native Americans as Indians. Even some Native Americans call themselves Indians, but most of them prefer using their legitimate tribal names. To avoid offending, you should ask a Native American if he or she minds being called Indian. I am using the term here to avoid confusing our non-American readers, and I mean no offense to my Native American neighbors.

The terms Native American and Indian are both misleading, as they suggest a homogeneous population. The original inhabitants of the United States at the time of the European invasion were composed of hundreds of different tribes. Many of the tribes did not share a common language or similar culture. In fact, some of the tribes were constantly at war with each other. Perhaps that is why many Native Americans today do not call themselves Indians or Native Americans, but prefer to say for example, "We are the Lakota people. Some call us the Sioux."

© Michelle Leco

© Michelle Leco

A statue of a Native American Indian adorned in a ceremonial costume.

There are many diverse tribes

When the first European explorers arrived in this land, Native American tribes populated every part of the continent. Early settlers found the Delawares, Iroquois, Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, Algonquin and other tribes in the northeastern part of the USA. They met Seminoles, Cherokees and Miccusuki in the south. The Spanish explorers in California encountered the Shoshone, Paiute, Cahuilla, and Mewuk and additional tribes. By the nineteenth century, the European invaders began to migrate westward and to push the Native American tribes off of their traditional homelands. This was the period of our shameful western Indian wars against the Apache, Sioux, Comanches and others. Superior numbers and advanced technology soon prevailed, and the few surviving natives were forcibly restricted to small areas known as Indian reservations.

Today, there are hundreds of Indian reservations across the USA, and many descendants of the Native Americans still live on them. Some tribes have managed to profit from the natural resources on their lands and the inhabitants have become rather wealthy. On other reservations, the residents exploit thriving tourist businesses. Unfortunately, many tribes own few resources and the inhabitants of their reservations live in poverty.