Monnas, Lisa. Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings, 1300-1550.London: Yale University Press,2008.

Musin, Alexander. “Russian Medieval Culture as an Area of Preservation of Byzantine Civilization,” in T owards rewriting? : new approaches to Byzantine archaeology and art : proceedings of the symposium on Byzantine art and archaeology, Cracow, September 8-10, 2008,ed Piotr L Grotowski; Sławomir Skrzyniarz,11-44.Warsaw : The Polish Society of Oriental Art, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, Jagiellonian University, the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Cracow, 2010.

Muthesius, Anna. Studies in silk in Byzantium. London : Pindar Press, 2004.

Netherton, Robin and R. Owen- Crocker, Medieval Clothing and Textiles 1.Woodbridge:Boydell Press,2005.

Parani, Maria G. Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography 11th -15th Centuries.Leiden:Brill,2003.

Rautman, Marcus.Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire. London: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Sociocultural Theory In Anthropology Indiana University “Biographies: Clifford Geertz.” Accessed January12, 2015. http://www.indiana.edu/~wanthro/theory_pages/Geertz.htm.

Stecker, Pamela. The Fashion Design Manual. Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1996.

The Byzantine and Christian Museum. “Textile.”.Last modified January 12, 2015. http://www.byzantinemuseum.gr/en/collections/textiles/

Timothy Miller, “Constantine IX: Typikon of Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos.” in Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments, ed. John Thomas and Angela Constantinides Hero.Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2001)

Tonemann, Peter. The Meander Valley: A Historical Geography from Antiquity to Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Tsougarakis, I. Nickiphoros and Peter Lock, A Companion to Latin Greece. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub, 2014.

Byzantine Textile: Splendour and Reflections

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: 7th Century AD: Hestia polyolbos, Egypt (Hestia Tapestry; slightly damaged. Height 1.13 X 1,377 meters. Wool on linen. Collection Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, USA.[68]

Figure 2: Fragment of a Wall Hanging, Coptic (Byzantine Egypt), 4th–6th century

Wool and linen, 12 3/4 x 24 3/8 in. (32.5 x 61.8 cm)[69]

Figure 3: Fragment (of a Hanging?) with Jewelled Border, 4th-6th century, Creation Place: Ancient & Byzantine World, Africa, Egypt (Ancient),Early Byzantine, Wool and linen, Woven, tapestry weave,47 x 17 cm (18 1/2 x 6 11/16 in.)[70]

Figure 4: Annunciation, 8th–9th century. Made in Alexandria or Egypt, Syria, Constantinople (?). Weft-faced compound twill (samit) in polychrome silk. Vatican Museums, Vatican City (61231)[71]

Figure 5: Tapestry Square with the Head of Spring, 4th–5th century; Early Byzantine Egyptian Polychrome wool, linen; 9 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (23.5 x 25.1 cm)[72]

Figure 6: Textile fragment, Coptic period (3rd–12th century), probably 6th–7th century

Egypt, Silk, linen; plain weave, embroidered. This scene is reminiscent of depictions of emperors and serves as a rare example of silk embroidery on undyed linen. Only the beige and blue colours survive.[73]

Figure 7: Christian Egypt and Coptic art, 6th c., 55Χ50, Child’s woollen tunic decorated with woven human figures, animals and birds.[74]

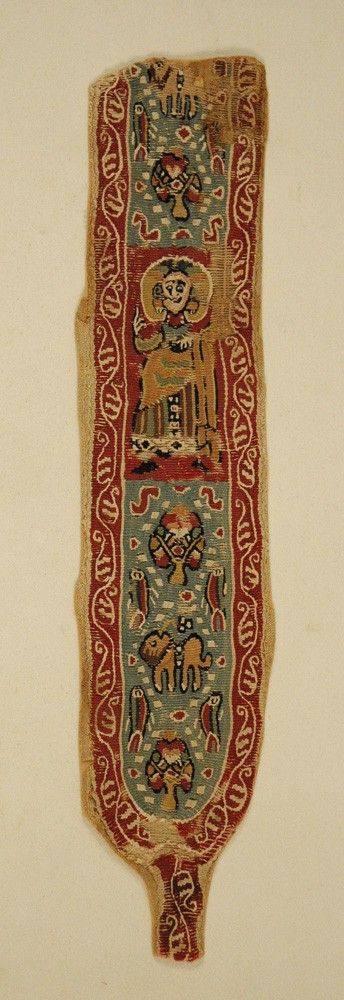

Figure 8: Christian Egypt Coptic Art, 6th - 8th c., 41Χ8, the polychrome, woven band was part of the decoration on a chiton. Usually a linen chiton had bands sewn in a vertical arrangement on front and back as well as towards the ends of the sleeves. These bands were sometimes decorated with purely geometric patterns and sometimes had depictions with human figures, animals and plants. In this case the depictions are divided into three sections. In the middle one a male figure, perhaps (as he has a large halo round his head) representing a saint, is depicted standing. The other two sections depict, in highly stylized form: a four-legged animal, two trees and fish with S-shaped symbols in between which may indicate the element of water.[75]

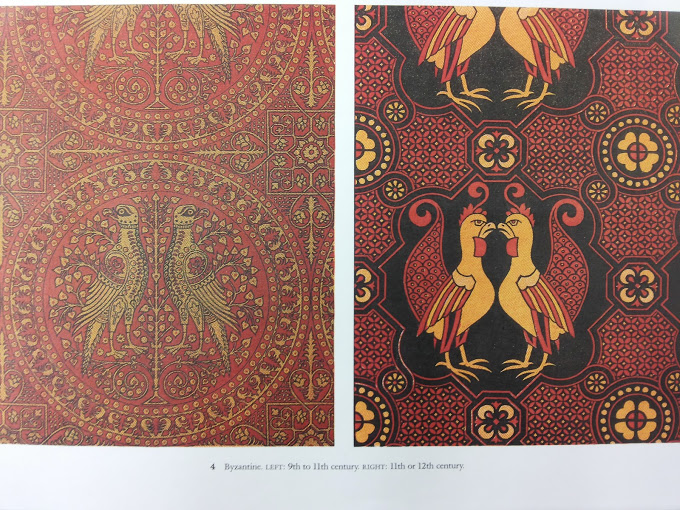

Figure 9: Byzantine fabric, Left 9th to 11th century Right 11th or 12th century[76]

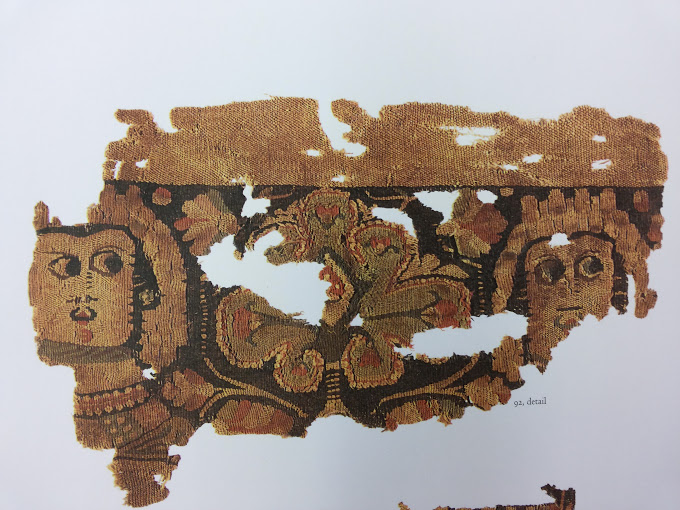

Figure 10:Fragments of Textile Hanging with Female Busts,Egypt,Byzantine 5th-6th century, wool and linen,10-18 cm.[77]

Figure 11: Egypt, Tunic, woven wool, with appliqué ornaments tapestry-woven in coloured wool and linen on linen warps,670-870. The bands and stripes that commonly decorate Coptic tunics are possibly Roman in derivation.[78]

Figure 12: Minor Sakkos of the Metropolitan Photios,Byzantine Constantinople 14th century. Silk Satin textile embroidered with silver, silver gilt and coloured thread with pearls.[79]

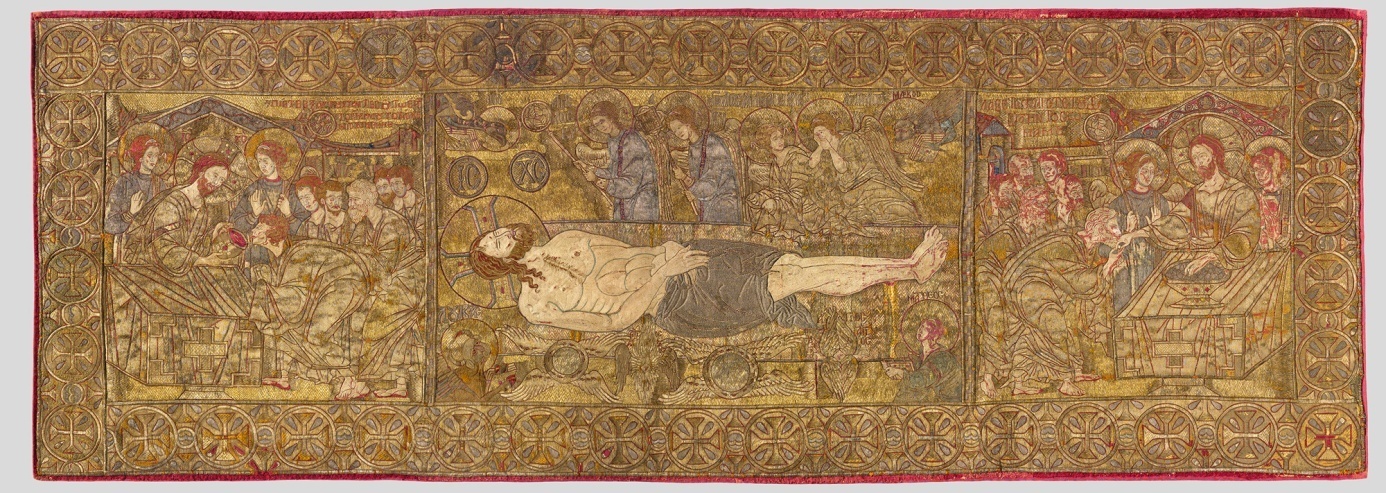

Figure 13:Epitaphios as a liturgical cloth comes from the Christian aer or Katapetasma veil and is already known by the end of the twelve century.Thessaloniki,14th century, Silk and Linen,72x200cm.[80]

Figure 14: Auxerre, Byzantine silk panel with spread eagle,11th century,Eusebe Church.[81]

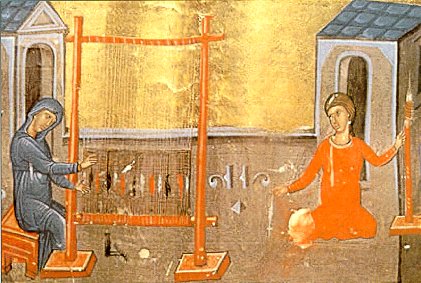

Figure 15: Jerusalem, Patriarchal Library, ms. Taphou 5 (Book of Job), fol. 234b, Women spinning and weaving (late 13th century).[82]

[1] Agnes Geijer , A History of Textile Art: A Selective Account ( Stockholm and London: Pasold Research Fund, 1979),129.

[2]Especially The Coptic textiles constitute a special category of their own. They are associated with the Christians in Egypt, who were directly linked with Byzantium until 641, the year in which the empire lost the Egyptian provinces for good when they passed to the Arabs. In fact many works are still described as ‘Coptic’ even if they can be dated later than that. The term ‘Copt’ is derived from an Arabic corruption of the Greek word for Egyptian and is used to refer to an Egyptian Christian. The Coptic textiles were found in excavations of Christian tombs in Egypt and were preserved thanks to the special climatic conditions in the region. They are mostly made of linen with scenes embroidered or woven in coloured wools. “Textile,” The Byzantine and Christian Museum, accessed January 12,2015,http://www.byzantinemuseum.gr/en/collections/textiles/.

[3]Deborah A. Deacon and Paula E. Calvin, War Imagery in Women's Textiles: An International Study of Weaving, Knitting, Sewing, Quilting, Rug Making and Other Fabric Arts (North Carolina: McFarland Company, 2014),160.

[4] Angeliki E. Laiou and Cecile Morrison, The Byzantine Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,2007) ,78

[5] Robin Netherton and R. Owen- Crocker, Medieval Clothing and Textiles 1(Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005),70.

[6] Timothy Dawson, Property, Practicality and Pleasure: the Parameters of Women’s Dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200,” in Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800-1200, ed. Lynda Garland (Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006), 53.

[7] Ibid., 53.

[8]Michael Grünbart, Material Culture and Well-Being in Byzantium (400-1453) : Proceedings of the International Conference (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2007), 162.

[9] Guglielmo Cavallo,The Byzantines (Chicago:The University of Chicago Press,1997),51.

[10]Ibid. ,51.

[11] Timothy Dawson, “Property, Practicality and Pleasure: the Parameters of Women’s Dress in Bzyantium, A.D.1000-1200,” in Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800-1200, ed. Lynda Garland (Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Company,2006),53.

[12] Hugh N. Kennedy, The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East (Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006),101.