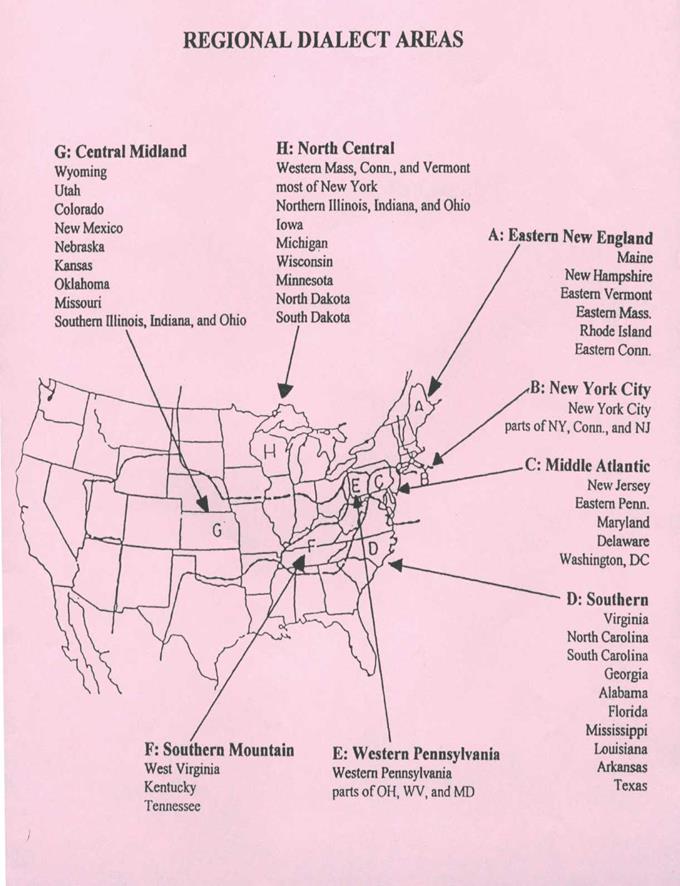

Study the following diagnostics of the regional varieties of American English.

Be prepared to speak about Eastern New England, Middle Atlantic, Southern, North Central and Southern Mountain varieties.

REGIONAL DIALECTS OF AMERICAN ENGLISH

1. Eastern New England

(1) non-rhotic: car, cart have no [r]

(2) when r is not pronounced, it is often replaced by schwa: [kaq], [foq] car, four or long vowel [ka:], [fo:]. Note: length marked by:

(3) linking-r

(4) intrusive-r

(5) orange, etc. with [Q]

(6) front [a] rather than [ Q ] in words in which r is not pronounced (also some other words such as bath)

(7) tune, due, new with [j], but this is not consistent

(8) occasionally [hw]

2. Middle Atlantic

(1) rhotic (consistently, unlike NYC)

(2) orange, etc. with [ Q ]

3. Southern

(1) non-rhotic

(2) when r is not pronounced, it is often replaced by schwa or the vowel is lengthened:

four [foq],[fo:],[fL]

(3) linking-r, but rather rarely

(4) intrusive-r, but rarely

(5) orange, etc. with [Q]

(6) tune, due, new with [j]

(7) diphthongization of monophthongs, can't [keInt]

(8) and the reverse: monophthongization of diphthongs, mile |ma:l]. Note: monophthongization before [r] is not a diagnostic as, depending on the style of speech, our, etc. can be pronounced either [aVr] or [[ar] in most dialects of English.

(9) word-finally [ I ] rather than [i]

(10) sometimes [hw]

(11) before a nasal consonant [F] and [I] are pronounced the same: as a nasalized [I],

pen = pin [pIn]

(12) the words greasy and grease are pronounced with [z] rather than [s]

4. North Central

(1) rhotic

(2) [ F ] instead of [x] before r, [m F ri] marry. So, in this dialect marry = merry = Mary.

(3) [hw] is frequent but limited to the older generation

(4) Canadian [EV] for [aV], but only in the areas bordering on Canada, mouse [mEVs]

(5) often [ar] rather than [Qr], car [kar]

(6) Iowa and further West: [Q] rather than [O] in words such as caught, that is, caught = cot. The vowel [O] is thus restricted to the context of [r], as in pour. Note: some speakers make a distinction between cot [Q] and caught [P]. The vowel [P] is like [Q] but it has slight lip rounding. Since the distinction is so small, it is very difficult to hear the difference between [Q] and [P]

5. Southern Mountain

(1) rhotic

(2) diphthongization of monophthongs, can't [keint]

(3) and the reverse: monophthongization of diphthongs, mile [ma:l]

(4) word-finally [ I] rather than [i]

(5) sometimes centralization of round vowels: [oV]

(6) the words greasy and grease are pronounced with [z] rather than [s].

Exercise 2 0

Study carefully the diagnostic characteristic of RP from this scheme and prepare to speak about diagnostic characteristic of GenAm.

1. Non-rhotic, that is, no postvocalic-r (as in ENE, NYC and Southern)

car /ka:/, cart /ka:t/

2. Back /a:/ and not /a:/, i.e. unlike ENE (examples above)

3. Development of /q/ before r (no matter whether the letter r is pronounced or not):

/Iq/, /Vq/, /aIq/

Compare:

example RP American (most dialects)

hear hiq hir

hearing hiqriN hiriN

tour tVq tVr

fire faIq faIr

4. The use of /P/ in words spelled with o where most American dialects have /Q/

Compare:

example RP American

pot pPt pQt

5. /j/ in tune, due, new type of words:

/tjun/, /dju/, /nju/

6. /a:/ where American has /x/

Compare:

example RP American

pass pRs pxs

Master Card mRstq kRd mxstqr kQrd

can’t kRnt kxnt or kxt (the /x/ is nasalized;

the /n/ isn’t pronounced)

7. The American diphthong /oV/ is represented as /EV/

Compare:

example RP American

go gEV goV

note nEVt noVt

8. /L/ where American has /Q/ or /O/

Compare:

example RP American

caught kLt kQt or kOt (or some intermediate vowel)

water wLtq wQtqr or wOtqr (or some intermediate vowel)

NOTE: RP does not have the flap /r/.

9. The distinction between the stressed schwa /A/ and the unstressed schwa /q/

Compare:

example RP American

cup kAp kqp

hurry hArI hqri

banana bqnRnq bqnxnq note: means nasalization

NOTE: RP has final /I/, like Southern, and not /i/. Also, RP has no nasalization of vowels before nasal consonants, but that's a little detail.

10. /e/ for American /F/

Compare:

example RP American

bet bet bFt

ten ten tFn (the vowel is nasalized)

Exercise 2 1

Study the sample sentence as pronounced in different regional varieties. Single out the diagnostic phonetic features of these regional varieties.

1. Eastern New England

/ wqn hQrqd reIni deI / rxDq leIt In fFbjuFri / wi stRtId saVT/

2. Middle Atlantic

/ wqn hQrqd reIni deI / rQDqr leIt In fFbruFri / wi stQrtqd saVT /

3. Southern

/ wqn hQrqd reInI deI / rQDq leIt In fFbjuFrI / wi stRrId sxVT/

4. North Central

/ wqn hOrqd reIni deI / rxDqr leIt In fFbjuFri / wi stQrtqd saVT /

5. Southern Mountain

/ wqn hOrqd reInI deI / rxDqr leIt In fFbjuFrI / wi stQrtqd saVT /

6. RP (Received Pronunciation, British English)

/ wAn hPrId deI / rRDq leIt In febrVqrI / wi stRtId saVT/

PART 3

Recommended Literature

for the American English Course

1. Швейцер А.Д. Литературный английский язык в США и Англии. – М.: Эдиториал УРСС, 2003. – 200 с.

2. Eakins B., Eakins G. Sex Differences in Human Communication. – Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978

3. Fisher J. N. L. Social Influences on the Choice of a Linguistic Variant // Word. – 1958

4. Goodwin M.H. He – Said – She – Said: Talk as Social Organization among Black Children. – Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990

5. Gramley S. E., Patzold K-M. A Survey of Modern English. – London and New York: Routledge, 1992. – 498 p.

6. Jespersen O. Language: Its Nature, Development and Origin. – London: Allen and Unwin, 1922

7. Labov, W. The Social Stratification of English in New York City. – Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1966

8. Labov, The Intersection of Sex and Social Class in the Course of Linguistic Change // Language Variation and Change. – 1990

9. W. Lakoff, R. Language and Women’s Place // Language in Society. – 1973

10. Maltz D., Borker R. A Cultural Approach to Male-Female Miscommunication // Language and Social Identity. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. – P. 195-216

11. McConnel-Ginet, S. Language and Gender // Linguistics: The Cambridge Survey. – New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988. – Vol. IV – P. 75-99

12. Miller, C. Who Says What to Whom?: Empirical Studies of Language and Gender // The Women and Language Debate. – New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1994. – P. 265-279

13. Spender D. Man Make Language. – Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980

14. Tannen, D. That’s Not What I Mean! How Conversational Style Makes or Breaks Relationships. – New York: Ballantine, 1987

15. Tannen, D. You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. – New York: Ballantine, 1990

16. Quirk R., Greenbaum, S., Leech G., Svartvik J. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. – London: Longman, 1985

17. Wolfram, W. A Linguistic Description of Detroit Negro Speech. – Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1969

18. Wolfram W., Schilling-Estes N. American English: Dialects and Variation. – Malden, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 1998. – 398 p.

List of Abbreviations

1. AmE – American English

2. BrE – British English

3. GenAm – General American

4. RP – Received Pronunciation

Glossary

Leveling. The reduction of distinct forms within a grammatical paradigm, as in the use of was with all subject persons and numbers for past tense be

(e.g. I/you/(s)he/we/you/they was).

Canadian raising. The raising of the nucleus of the /aI/ and /aV/ diphthongs to /q/, as in /rqIt/ for right or /qVt/ for out.

Creole language. A special contact language in which the primary vocabulary of one language is superimposed upon a specially adapted, somewhat restricted grammatical structure; this language system may be used as a native language.

Cultural difference theory. An approach to language and gender that views differences in men’s and women’s speech as a function of differential socio-cultural experiences by men and women.

Deficit theory. With reference to language and gender studies, the theory that considers female language traits as deficient versions of male language.

Dialect. A variety of the language associated with a particular regional or social group.

Dialect awareness programs. Activities conducted by linguists and community members that are intended to promote an understanding of and appreciation for language variation.

Dominance theory. With respect to language and gender, the consideration of male-female language differences as the result of power differences between men and women.

Double modal. The co-occurrence of two or even three modal forms within a single verb phrase, as in They might could do it or They might oughta should do it.

Flap. A sound made by rapidly tapping the tip of the tongue to the alveolar ridge, as in the usual American English pronunciation of t in Betty /bFdi/ or d in ladder /lxdqr/.

Formal Standard English. The variety of English prescribed as the standard by language authorities; found primarily in written language and the most formal spoken language (e.g. spoken language which is based on a written form of the language).

Gender. The complex of social, cultural and psychological factors that surround sex; contrasted with sex as biological attribute.

Generic he. The use of the masculine pronoun he for referents which can be either male or female; for example, If a student wants to pass the course, he should study. The noun man historically has also been used as a generic, as in Man shall not live by bread alone.

Hypercorrection. The extension of a language form beyond its regular linguistic boundaries when a speaker feels a need to use extremely standard or “correct” forms.

Informal Standard English. The spoken variety of English considered socially acceptable in mainstream contexts; typically characterized by the absence of socially stigmatized linguistic structures.

Multiple negation. The marking of negation at more than one point in a sentence (e.g. They didn’t do nothing about nobody.). Also called double negation, negative concord.

Network Standard. A variety of English relatively free of marked regional characteristics; the ideal norm aimed for by national radio and television network announcers.

Nonstandard. With reference to language forms, socially stigmatized through association with socially disfavoured groups.

Nonstandard dialect. A socially disfavoured dialect of a language.

Pidgin language. A language used primarily as a trade language among speakers of different languages; has no native speakers. The vocabulary of a pidgin language is taken primarily from a superordinate language, and the grammar is drastically reduced.

Prescriptive standard English. The variety deemed standard by grammar books and other recognized language “authorities”.

Regional standard English. A variety considered to be standard for a given regional area; for example, the Eastern New England standard or the Southern standard.

Schwa. A mid central vowel symbolized as /q/; for example, the first vowel in appear /q`pir/. Generally occurs in unstressed syllables in English.

Socially prestigious. Socially favoured; with respect to language forms or patterns, items associated with high-status groups.

Socially stigmatized. Socially disfavoured, as in a language form or pattern associated with low-status groups (e.g. He didn’t do nothing to nobody).

Standard American English. A widely socially accepted variety of English that is held to be the linguistic norm and that is relatively unmarked with respect to regional characteristics of English.

Superstandard English. Forms or styles of speech which are more standard than called for in everyday conversation (It is I who shall write this).

Superstrate. A language spoken by a dominant group which influences the structure of the language of a subordinate group of speakers. Often used to refer to the dominant language upon which a creole language is based.