Alexander Stoddart

This question occupies both the would-be innovators and the traditionalists like Alexander Stoddart, a monumental sculptor whose works stand in public places around the world as well as in the Queen’s gallery in Buckingham Palace.

Scruton to Stoddart: A defender of conceptual art might say that an idea can be beautiful.

So there is nothing wrong with conceptual art as such.

Stoddart: Yes, but this is in everybody’s field of endeavor. The lawyer can come up with a beautiful idea. You know, the statesman, the medic, let’s cure cancer, a beautiful idea, but he doesn’t say he’s an artist on the back of that.

Conceptual art is entirely word bound. It is an art that is exhausted in its verbal description.

You really just need to say “half a cow in a tank of formaldehyde” and you are really all the way there.

The object itself can then be dumped. Tracey Emin’s bed is a perfect example of that.

If you walked past some skip in some scheme and you saw that bed lying there you would walk on.

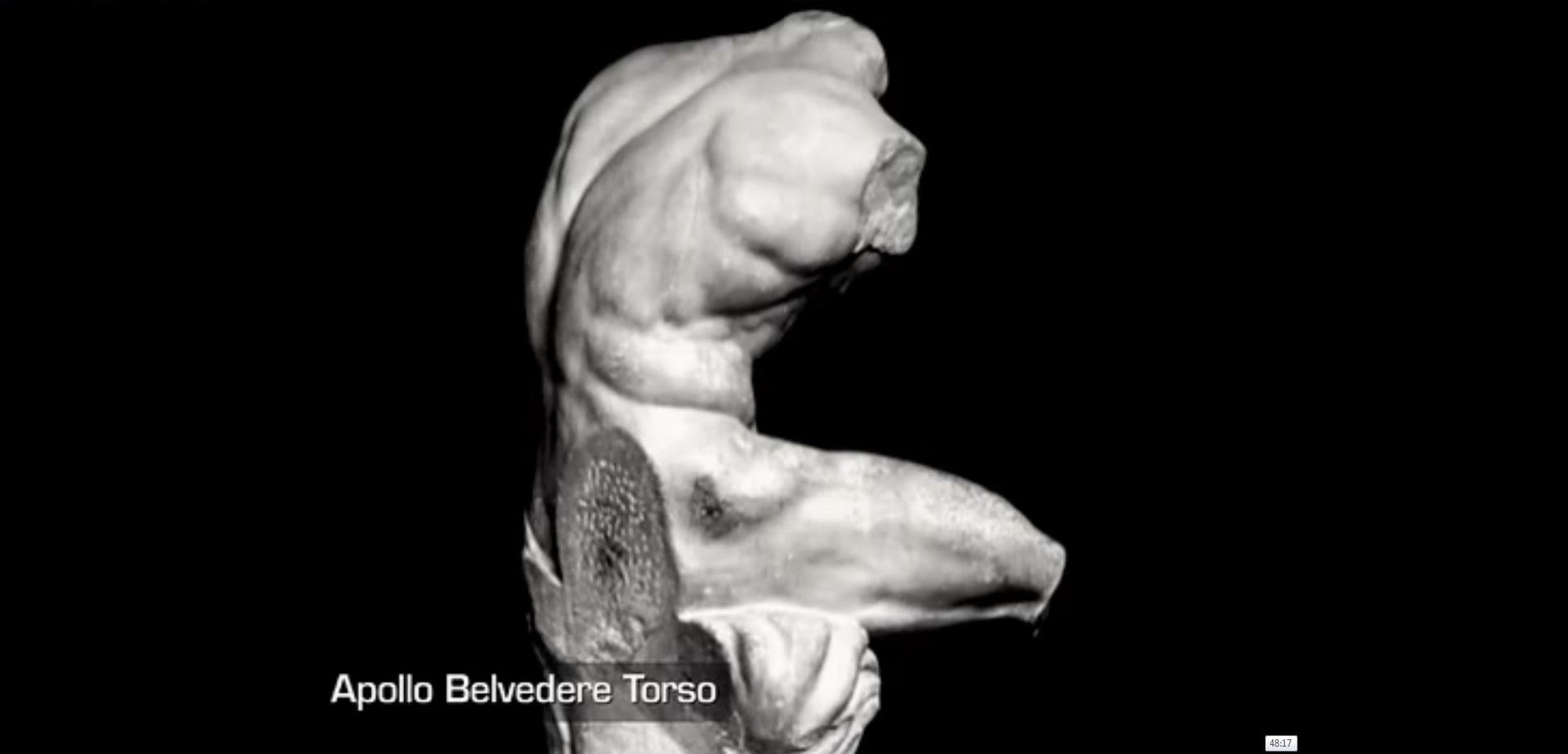

But of course if you saw even just the torso of the Apollo Belvedere lying in that skip you would be arrested by it and you may indeed climb in and try to retrieve it.

Many students come to me from sculpture departments, secretly of course, because they don’t want to tell their tutors that they’ve come to truck with the enemy.

And they say I tried to become a modeler(?) figure and I modeled it in clay and then a tutor came up and told me to cut it in half and dump some diarrhea on top of it and that would make it interesting.

Scruton: It’s what I feel about the standardized desecration that passes for art these days and actually it is a kind of immorality because it is an attempt to obliterate meaning from the human form in some way.

Stoddart: It’s an attempt to obliterate knowledge.

The art establishment has turned away from the old curriculum which put beauty and art at the top of the agenda.

Those like Alexander Stoddart who try to restore the age-old connection between the beautiful and the sacred are seen as old-fashioned and absurd.

The same kind of criticism is aimed at traditionalists in architecture.

One target is Leon Krier, architect of the Prince of Wale’s town of Poundbury.

Designing modest streets, laid out in traditional ways using the well-tried and much loved details that have served us down the centuries, Leon Krier has created a genuine settlement.

The proportions are human proportions. The details are restful to the eye.

This is not great or original architecture nor does it try to be.

It is a modest attempt to get things right by following patterns and examples laid down by tradition.

This is not nostalgia, but knowledge passed on from age to age.

Architecture that doesn’t respect the past is not respecting the present because it is not respecting people’s primary need from architecture which is to build a long-standing home.

I have showed some of the ways in which artists and architects have followed the call of beauty.

In doing so, they have given our world meaning.

The masters of the past recognized that we have spiritual needs as well as animal appetites.

For Plato, beauty was a path to God.

While thinkers of the Enlightenment saw art and beauty as ways in which we save ourselves from meaningless routines and rise to a higher level.

But art turned its back on beauty. It became a slave to the consumer culture. Feeding our pleasures and addictions and wallowing in self-disgust.

That it seems to me is the lesson of the ugliest forms of modern art and architecture. They do not show reality, but take revenge on it.

Spoiling what might have been a home and leaving us to wander unconsoled and alienated in a spiritual desert.

Of course it is true that there is much in the world today that distracts and troubles us.

Our lives are full of leftovers. We battle through noise and distraction and nothing resolves.

The right response, however, is not to endorse this alienation, it is to look for the path back from the desert, one that will point us to a place where the real and the ideal may still exist in harmony.

In my own life, I have found my own path more easily through music than from any other artform.

Pergolesi was 26 when he wrote the Stabat Mater.

It describes the grief of the Holy Virgin beside the cross of the dying Christ.

All the suffering of the world is symbolized in its exquisite lines.

Given that Pergolesi was suffering from tuberculosis when he wrote the Stabat Mater, he is that son dying on the cross too.

In fact, he died within a few months of the work’s completion.

This is not a complex or ambitious piece of music.

Simply a heart-felt expression of the composer’s faith.

It shows the way deep and troubling emotions can achieve unity and freedom through music.

The voice of Mary is written for two singers.

The melody rises slowly, painfully resolving dissonance only to be gripped by another dissonance as the voices clash, representing the conflict and sorrow within her.

Singer – Here we have a very simple and sacred text. The mother stands grieving and weeping at the cross on which her son is hanging. That’s really all that you have to say.

And a completely unmusical person would immediately get the message that it’s a piece of grieving.

Scruton – The music takes over the words and makes them speak to you in another language in your own heart.

Singer – Well it means that today in our secular world it can move and delight without people having to know what it’s about.

Scruton – We learn without the theological apparatus that there is this thing called suffering and that it’s the destiny of all us but also that it’s not the end of all of us.

Conclusion

In this film I have described beauty as an essential resource.

Through the pursuit of beauty, we shape the world as a home and in doing so we both amplify our joys and find consolation for our sorrows.

Art and music shine a light of meaning on ordinary life and through them we are able to confront the things that trouble us and to find consolation and peace in their presence.

This capacity of beauty to redeem our suffering is one reason why beauty can be seen as a substitute for religion.

Why give priority to religion?

Why not say that religion is a beauty substitute?

Better still why describe the two as rivals?

The sacred and the beautiful stand side by side – two doors that open onto a single space and in that space we find our home.