The Third Earl of Shaftesbury

And one philosopher in particular set out to fill this vacuum, that is the Third Earl of Shaftesbury.

Science explains things, but thought Shaftesbury, its account of the world is in one way incomplete.

We can see the world from another perspective. Not seeking to use it or explain it.

But simply contemplating its appearance.

As we might contemplate a landscape or a flower.

The idea that the world is intrinsically meaningful, full of an enchantment that it needs no religious doctrine to perceive answered to a deep emotional need.

Beauty was not planted in the world by God, but discovered there by people. [Both!]

Shaftesbury’s idea encouraged the cult of beauty which raised the appreciation of art and nature to the place once occupied by God.

Beauty was to fill the God-shaped hole made by science.

Artists were no longer illustrators of the sacred stories who worked as servants of the Church.

They were discovering the stories for themselves by interpreting the secrets of nature.

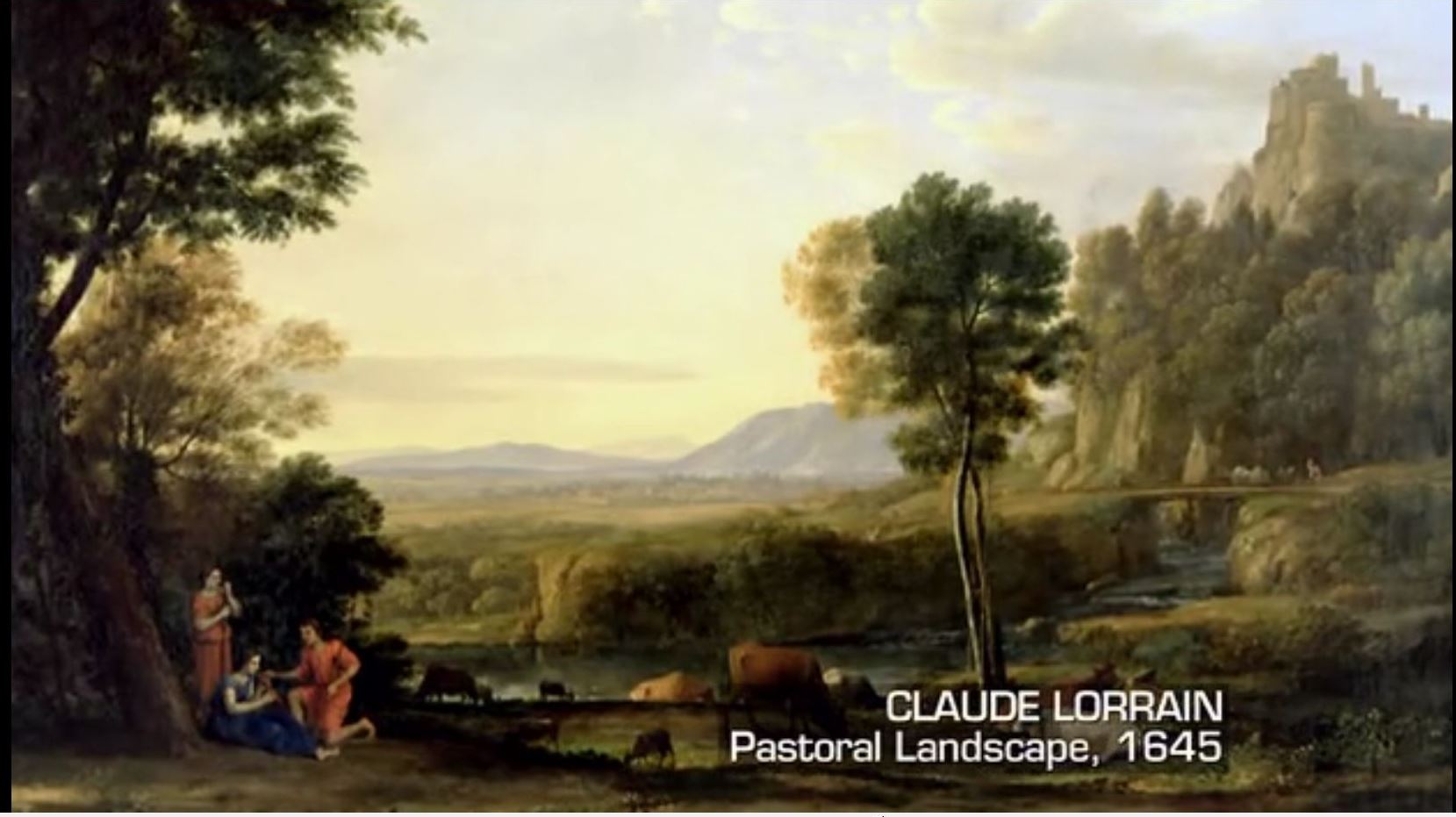

Landscapes which used to be mere backgrounds to holy images became foregrounds, with the human figure often lost in their folds.

But for Shaftesbury, it does not need a work of art to present us with the beauty of the world.

We simply need to look on things with clear eyes and free emotions.

Shaftesbury is telling us to stop using things; stop explaining and exploiting them, but look at them instead.

Then we will understand what they mean.

The message of the flower is the flower.

Zen Buddhists have said similar things – only by leaving all our interests and business to one side do we encounter the real truth of the flower.

Seeing things that way, we discover their beauty.

The greatest philosopher of the Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant, was profoundly influenced by Shaftesbury’s idea.

Kant argued that the experience of beauty comes when we put our interests to one side. When we look on things not in order to use them for our purposes or to explain how they work or to satisfy some need or appetite but simply to absorb them and to endorse what they are.

Consider the joy you might feel when you hold a friend’s baby in your arms.

You don’t want to do anything with the baby. You don’t want to eat it; to put it to any use.

Or to conduct scientific experiments on it.

You want simply to look at it and to feel the great surge of delight that comes when you focus all your thoughts on this baby and none at all on yourself.

That is what Kant described as a disinterested attitude and it is the attitude that underlies our experience of beauty.

To explain this is extremely difficult, because if you haven’t experienced it you don’t really know what it is.

But everybody listening to a beautiful piece of music, looking at a sublime landscape, reading a poem that seems to contain the essence of the thing it describes, everybody in an experience like that says “Yes, this is enough.”

But why is this experience so important?

The encounter with beauty is so vivid, so immediate, so personal that it seems hardly to belong to the ordinary world.

Yet beauty shines on us from ordinary things.

Is it a feature of the world, or a figment of the imagination?

Most of the time our lives are organized by our everyday concerns.

But every now and then, we find ourselves jolted out of our complacency by something vastly more important than our immediate desires and interests; something not of this world.

From Plato to Kant, philosophers have tried to capture the peculiar way in which beauty dawns on us.

Like a sudden ray of sunlight, or a surge of love.

For Plato, the only explanation of such an experience was its transcendental origin.

It speaks to us like the voice of God.

And Kant too, in a much more sober way, thinks that the experience of beauty connects us with the ultimate mystery of being.

Through beauty we are brought into the presence of the sacred.

We can understand what such philosopher’s mean if we reflect on what we feel in the presence of death; especially the death of someone loved.

We look with awe upon the human body from which the life has fled.

We are reluctant to touch the dead body. We see it as not properly a part of our world.

Almost a visitor from some other sphere.

And the same sense of the transcendental arises in the same experience that inspired Plato.

The experience of falling in love.

This too is a human universal and it is an experience of the strangest kind.

The face and body of the beloved are imbued with the intensest life.

But in one crucial respect, they are like the body of someone dead.

They seem not to belong in the everyday world.

Poets have expended thousands of words on this experience which no words seem entirely to capture.

But these great changes in the stream of life – the urge to unite with another person, the loss of someone loved, are moments that we understand as sacred.

If we look at the history of the idea of beauty, we see that philosophers and artists have had good reason to connect the beautiful and the sacred, and to see our need for beauty as something deep in our nature. Part of our longing for consolation in a world of danger, sorrow and distress.

Today many artists look on the idea of beauty with disdain.

A leftover from a way of living that has no real connection with the world that now surrounds us.

So there has been a desire to desecrate the experiences of death and sex.

By displaying them in trivial and impersonal ways; to destroy all sense of their spiritual significance.

Just as those who lose their religion have an urge to mock a faith that they have lost, so do artists today have an urge to treat human life in demeaning ways, and to mock the pursuit of beauty.

This willful desecration is also a denial of love; an attempt to remake the world as though love were no longer a part of it.

And this, it seems to me, is the most important feature of our post-modern culture.

That it is a loveless culture, determined to portray the human world as unlovable.

Of course, this habit of dwelling on the distressing side of human life isn’t new.

From the beginning of our civilization it has been one of the tasks of art to take what is most painful in the human condition and to redeem it in a work of beauty.

Art has the ability to redeem life by finding beauty even in the worst aspect of things.

Mantegna’s crucifixion, displaying the cruelest and most ugly of deaths achieves a kind of majesty and serenity.

It redeems the horror that it shows.

In the face of death, human beings can still show nobility, compassion and dignity.

And art helps us to accept death by presenting it in such a light.

What about things that are not tragic, but merely sordid or depraved?

Can art find beauty even here?

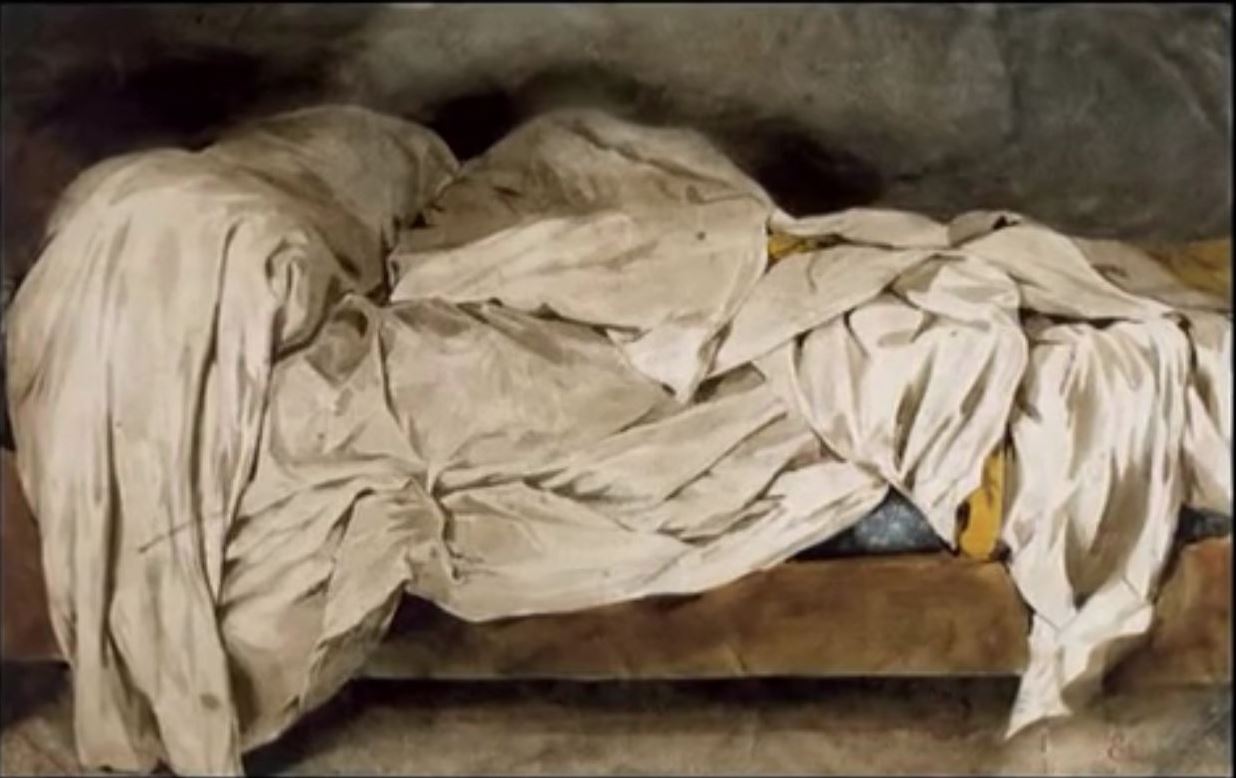

This painting by Delacroix shows us the artist’s bed in all its sordid disorder.

He too is bringing beauty to a thing that lacks it and bestowing a kind of blessing on his own emotional chaos.

Delacroix says see how these sweat-stained sheets record the troubled dreams the tormented energy of the person who has left them.

And how the light picks them out as though they are still animated by the sleeper.

The bed is transformed by the creative act, to become something else, a vivid symbol of the human condition and one which makes a bond between us and the artist.

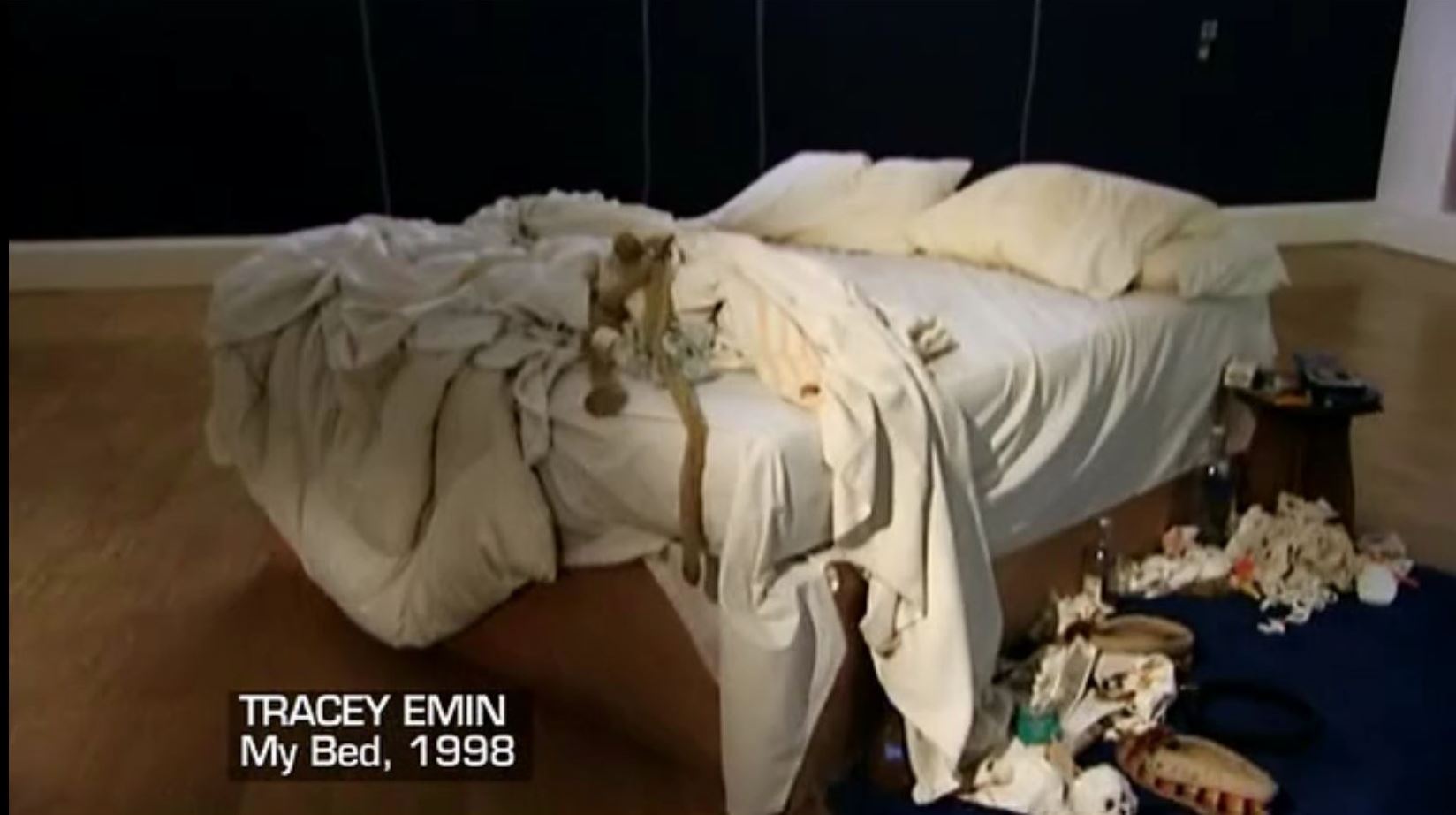

Tracey Emin’s My Bed in that way.

But there is all the difference in the world between a real work of art which makes ugliness beautiful and the fake work of art which shares the ugliness that it shows.

This is modern life presented in all its randomness and disorder.

Presenter: What is it that makes that art rather than just a rumpled bed?

Tracey Emin – Well the first thing that makes that art is because I say that it is.

Presenter: The second thing is that the Tate says that it is.

Tracey Emin: Yes.

Presenter: What do you want the viewer, the visitor to the gallery, to say? Presumably you don’t want him to say I think that it is beautiful?

Tracey Emin: No, actually no one’s actually said that, only me.

Presenter: Do you think this is beautiful?

Tracey Emin: Yeah, I do think it’s beautiful, otherwise I wouldn’t have shown it.

Scruton – How can this be a beautiful work of art if it makes no attempt to transform the raw material of an idea? It is just one sordid reality among others.

Literally, an unmade bed.

We are back with the question raised by Duchamp’s urinal whether anything can be art.