An Oak Tree – Michael Craig-Martin

Artist Michael Craig-Martin who taught several of the young British artists whose work dominates the artworld followed Duchamp’s example with his own seminal work called An Oak Tree.

This consists of a glass of water on a shelf with a text explaining why it is an oak tree.

Scruton – When I first entered St. Peters and confronted Michelangelo’s Pieta, for me it was a transporting experience.

My life was changed by this.

Do you think that someone could have the same experience with Duchamp’s urinal or your oak tree which is after all, a similar thing?

Michael Craig-Martin – I know that when I was a teenager and I first came upon Duchamp and I first came upon the ready-mades, I was absolutely stunned in amazement.

I don’t think people are overwhelmed by a sense of beauty when they see the urinal, it’s not meant to be beautiful, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t something about it that doesn’t captivate the imagination.

And I think that captivate the imagination is the key to what an artwork seeks to do.

Duchamp felt that art had become too interested in techniques, too interested in optics.

He felt that it had become intellectually and morally corrupt.

His reason for making an artwork that didn’t fit the system was not cynicism, it was in order to say that I’m trying to make an art that denies all of the things that people say art should have because I’m trying to say that the central question of art rests somewhere else.

I take the point that things had to change.

But what was Duchamp trying to change them to?

I’m sure he had no idea how central the thing was that he had stumbled upon – essentially that a work of art is a work of art because we think of it as such.

I also think it is important to say that the notion of beauty has been extended.

Part of the function of the artist is to make someone see something as beautiful something no one thought beautiful up until then.

Like a can of shit?

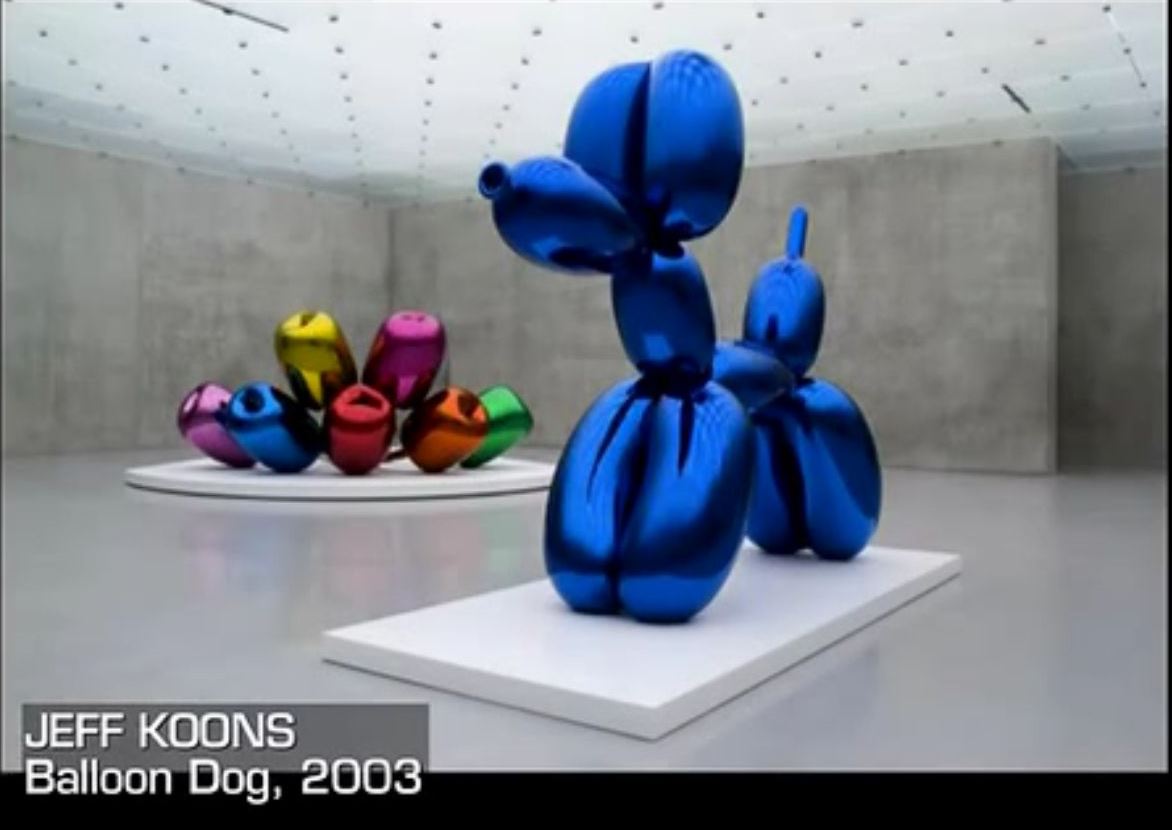

I’m not sure that it’s beautiful, but you see if you take an example of something that is not trying to be beautiful, if you take say Jeff Koons, Jeff Koons has done some things that are truly astoundingly beautiful.

It looks like so much kitsch to me; kitsch with sugar on.

This is the subject matter of his work, not the substance of his work.

What is the use of this art?

What does it help people to do?

This kind of art allows people to see the world in which they are living in a way that allows them to see more meaning in it.

It’s not an ideal world, some other place.

But of the here and now – living more at ease in the world that they are given.

Scruton

So the world of today shows us the world as it is – the here and now with all its imperfections.

But is the result really art?

Surely something is not a work of artjust because it offers us a slice of reality, ugliness included, and calls itself art.

Art needs creativity and creativity is about sharing.

It is a call to others to see the world as the artist sees it.

That is why we find beauty in the naïve art of children.

Children are not giving us ideas in the place of creative images.

Nor are they wallowing in ugliness.

They are trying to affirm the world as they see it and to share what they feel.

Something of the child’s pure delight in creation survives in every true work of art.

But creativity is not enough.

The skill of the true artist is to show the real in the light of the ideal and so transfigure it.

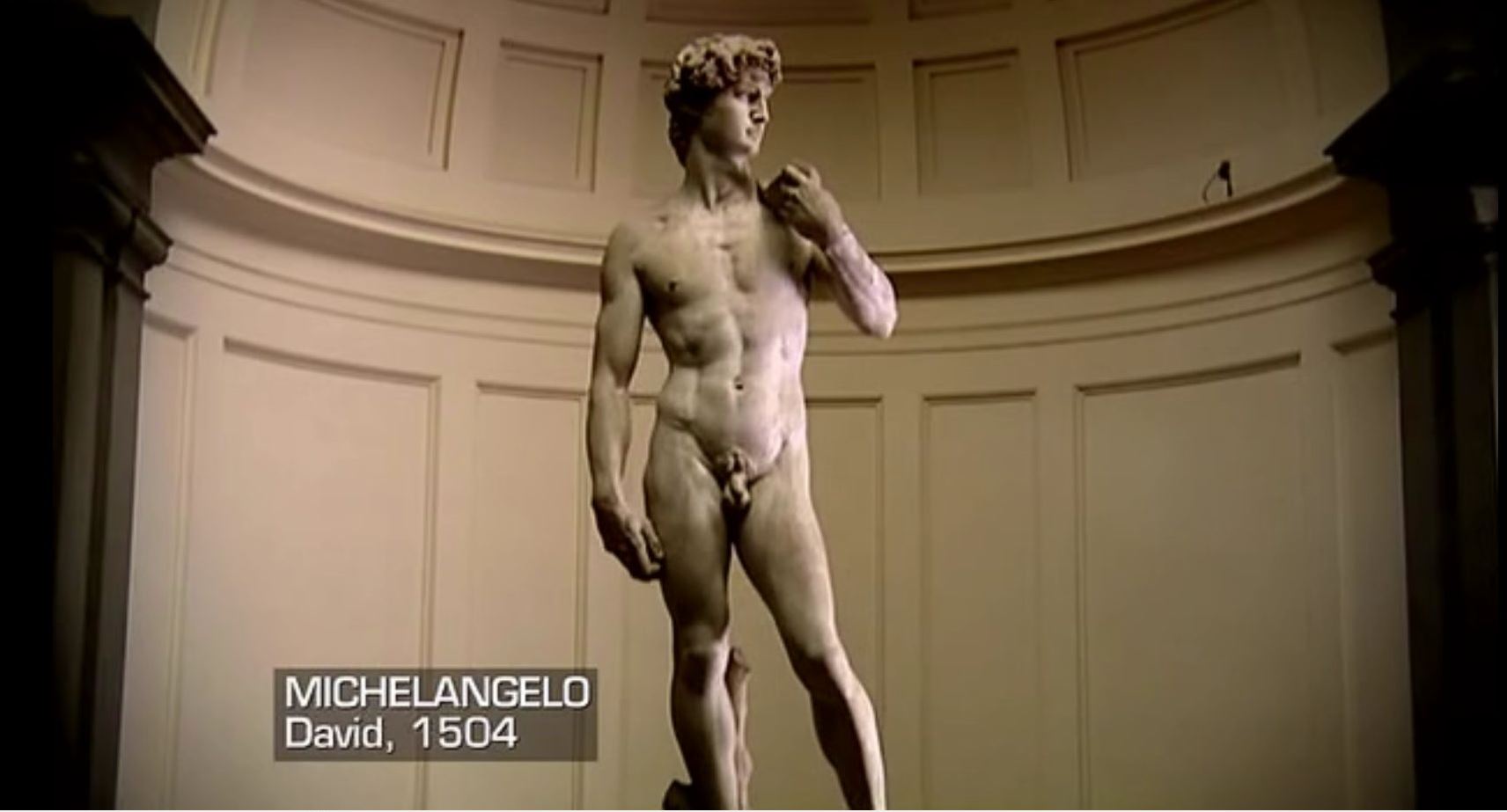

This is what Michelangelo achieves in his great portrayal of David.

But a concrete cast of David is not beautiful at all for it lacks the essential ingredient of creativity.

Discussions such as this are often regarded as dangerous.

In our democratic culture, people often think it threatening to judge another person’s taste.

Some are even offended by the suggestion that there is a difference between good and bad taste.

Or that it matters what you look at, or read, or listen to.

But this doesn’t help anybody.

There are standards of beauty which have a firm base in human nature and we need to look for them and build them into our lives.

[R - We have the ability to perceive realities in math and in beauty]

Maybe people have lost their faith in beauty because they have lost their belief in ideals.

All there is, they are tempted to think, is the world of appetite.

There are no values other than utilitarian ones.

Something has a value if it has a use.

And what’s the use of beauty?

Oscar Wilde wrote:

“All art is absolutely useless.”

Who intended his remark as praise.

For Wilde, beauty was a value higher than usefulness.

People need useless things, just as much, even more than, things with a use.

What is the use of:

A) Love

B) Friendship

C) Worship

None whatsoever.

And the same goes for beauty.

Our consumer society puts usefulness first, and beauty is no better than a side effect.

Since art is useless, it doesn’t matter what you read, what you look at, what you listen to.

We are besieged by messages on every side, titillated, tempted by appetite, never addressed and that is one reason why beauty is disappearing from our world.

Wordsworth

“Getting and spending we lay waste our powers.”

In our culture today, the advert is more important than the work of art.

And artworks often try to capture our attention as adverts do, by being brash or outrageous.

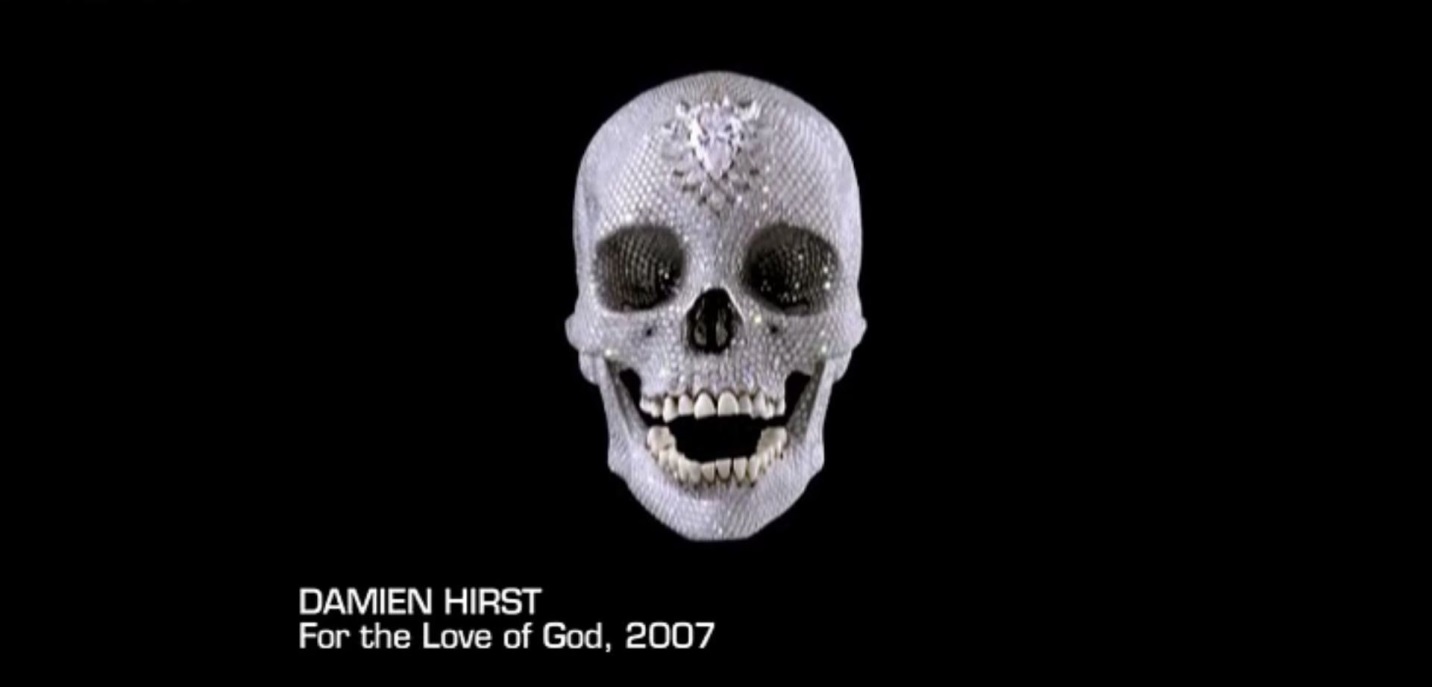

E.g., Damien Hurst – For the Love of God.

Like adverts, today’s works of art aim to create a brand.

Even if they have no product to sell except themselves.

Beauty is assailed from two directions:

By the cult of ugliness in the arts, and by the cult of utility in everyday life.

Architecture

These two cults come together in the world of modern architecture.

At the turn of the twentieth century, architects like artists began to be impatient with beauty and to put utility in its place.

Louis Sullivan

The American architect, Louis Sullivan, expressed the credo of the modernists when he said that form follows function.

In other words, stop thinking about the way a building looks and think instead about what it does.

Sullivan’s doctrine has been used to justify the greatest crime against beauty that the world has yet seen and that is the crime of modern architecture.

I grew up near Reading which was a charming Victorian town with terraced streets and Gothic churches crowned by elegant public buildings and smart hotels.

But in the 1960s, things began to change.

Here in the center, the homely streets were demolished to make way for office blocks, a bus station and carparks; all designed without consideration for beauty.

And the results prove that if you consider only utility, the things you build will soon be useless.

This building is boarded up because nobody has a use for it and nobody has a use for it because nobody wants to be in it.

Nobody wants to be in because the thing is so damned ugly.

Everywhere you turn there is ugliness and mutilation.

The offices and bus station have been abandoned.

Everything has been vandalized.

But we shouldn’t blame the vandals, this place was built by vandals and those who added the graffiti merely finished the job.

Most of our towns and cities have areas like this in which buildings erected merely for their utility have rapidly become useless.

Not that architects learned from the disaster.

When the public began to react against the brutal concrete style of the 1960s architects simply replaced it with a new kind of junk.

Glass walls hung on steel frames with absurd details that don’t match.

The result is another kind of failure to fit.

It is there simply to be demolished.

In the midst of all this desolation, we find a fragment of the streets which were destroyed.

Once a forge, now a café.

It is the last bit of life remaining and the life comes from the building.

Oscar Wilde again:

“All art is absolutely useless.

Put usefulness first and you lose it.

Put beauty first and what you do will be useful forever.”

It turns out that nothing is more useful than the useless.

We see this in traditional architecture with its decorative details.

Ornaments liberate us from the tyranny of the useful and satisfy our need for harmony.

In a strange way they make us feel at home.

They remind us that we have more than practical needs.

We are not just governed by animal appetites, like eating and sleeping, we have spiritual and moral needs too and if those needs go unsatisfied, so do we.

We all know what it is like, even in the everyday world, suddenly to be transported by the things we see.

From the ordinary world of our appetites to the illuminated sphere of contemplation.

A flash of sunlight, a remembered melody, the face of someone loved, these dawn on us in the most distracted moments and suddenly life is worthwhile.

These are timeless moments in which we feel the presence of another and higher world.

From the beginning of Western civilization, poets and philosophers have seen the experience of beauty as calling us to the divine.

Plato, writing in Athens in the fourth century BC, argued that beauty is the sign of another and higher order.

Beholding beauty with the eye of the mind you will be able to nourish true virtue and become the friend of God.

Plato was an idealist. He believed that human beings are pilgrims and passengers in this world, while always aspiring beyond it to the eternal realm where we will be united with God.

God exists in a transcendental world to which we humans aspire but which we cannot know directly.

But one way of glimpsing that heavenly sphere here below is through the experience of beauty.

This leads to a paradox.

For Plato, beauty was first and foremost, the beauty of the human face and human form.

The love of beauty, he thought, originates in Eros, a passion that all of us feel.

We would call this passion romantic love.

For Plato, Eros was a cosmic force which flows through us in the form of sexual desire.

But if human beauty arouses desire, how can it have anything to do with the divine?

Desire is for the individual living in this world.

It is an urgent passion.

Sexual desire presents us with a choice.

Adoration or appetite.

Love or lust.

Lust is about taking, but love is about giving.

Lust brings ugliness – the ugliness of human relations in which one person treats another as a disposable instrument.

To reach the source of beauty, we must overcome lust.

This longing without lust is what we mean today by Platonic love.

When we find beauty in a youthful person it is because we glimpse the light of eternity shining in those features from a heavenly source beyond this world.

The beautiful human form is an invitation to unite with it spiritually, not physically.

Our feeling for beauty is therefore a religious and not a sensual emotion.

This theory of Plato’s is astonishing.

Beauty is a visitor, he thought, from another world.

We can do nothing with it, save contemplate its pure radiance.

Anything else pollutes and desecrates it, destroying its sacred aura.

Plato’s theory may seem quaint to people today, but it is one of the most influential theories in history.

Throughout our civilization poets, storytellers, painters, priests and philosophers have been inspired by Plato’s views on sex and love.

Poetry

Those who have tried to express Plato’s theory on love.

Thomas Mallory - The Death of Arthur.

John Donne

Pearl Poet – Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Chaucer – The Knight’s Tale.

The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript

Dante

Spencer – The Fairy Queen.

The Birth of Venus – Botticelli

Goddess of erotic desire.

Venus looks on the world from a place beyond desire.

She is inviting us to transcend our earthly appetites and unite with her through the pure love of beauty.

Plato’s ideal – beauty is to be contemplated but not possessed.

Plato and Botticelli are telling us that real beauty lies beyond sexual desire, so we can find beauty not only in a desirable young person, but also in a face full of age, grief and wisdom. (30:11)

Such as Rembrandt painted.

The beauty of a face is a symbol of the life expressed in it.

It is flesh become spirit.

And in fixing our eyes on it, we seem to see right through into the soul.

Painters like Rembrandt are important for showing us that beauty is an ordinary, everyday kind of thing.

It lies all around us. We need only the eyes to see and the heart to feel.

The most ordinary event can be made into something beautiful by a painter who can see into the heart of things.

So long as a belief in a transcendental God was firmly anchored in the heart of our civilization artists and philosophers continued to think of beauty in Plato’s way.

Beauty was the revelation of God in the here and now.

This religious approach to the beautiful lasted for 2000 years.

But in the 17th century, the scientific revolution began to sow the seeds of doubt.

The medieval church accepted the ancient view that the Earth lies at the center of the universe.

Then Copernicus and Galileo proved that the Earth circles the Sun.

And Newton completed their work, describing a clockwork universe in which each moment follows mechanically from the one before.

This was the Enlightenment vision which described our world as though there were no place in it for gods and spirits.

No place for values and ideals.

No place for anything, save the regular clockwork movement which turned the Moon around the Earth and the Earth around the Sun for no purpose whatsoever.

At the heart of Newton’s universe is a God-shaped hole.

A spiritual vacuum.