6. Banerjea, J.N., Development of Ilindu Iconography, pp. 409-10.

XI

The Boar in Buddhism

In the Indian religious traditions there has been a tendency to adopt deities of one faith by another. The earliest evidence of this is available on the gateways of Sanchi stupas, where the figure of Gajalakshmi, is prominently shown. In the Hindu mythology, Lakshmi is believed to be the consort of Vishnu. But the appearance of Gajalakshmi in the Buddhist establishment and that too at such an early stage has its own importance in the history of the development of the religious thought in the country.

In the period that followed, and with the development of the various schools of Buddhism, particularly the Mahayana, several of the Hindu deities were adopted in the Buddhist faith. It is not that these deities were taken into the Buddhist fold for the sake of adoration or worship, but some of them after adoption, were relegated to Subordinate or even humiliating positions. For example, Ganesha happened to be the most popular of the Brahmanical deities. But he was brought into the Buddhist fold to be trampled upon by Aparajita, a Buddhist goddess. Shiva and Parvati were also conceived in the Buddhist pantheon, having been trampled upon by one or the other of the Buddhist deities.

Varaha on the other hand has been made to drive the chariot of Marichi. The Sadhanamala and other texts prescribe that the chariot of Marichi is driven by seven hogs.

Marichi, a Buddhist deity, is basically connected with the worship of sun, but has seven boars driving her vehicle. She is invoked by the Lamas of Tibet about the time of sunrise. She too like the Hindu Sun-god has a chariot drawn by seven boars, while that of the sun is stated to be driven by seven horses. Again the charioteer of the sun is Aruna who has no legs, but that of Marichi is either a goddess with no legs, of Rahu having only the head without a body.

There is another Buddhist goddess known as Vajravarahi who is sometimes equated with Marichi But the theory that Marichi and Vajravarahi are the same, cannot be supported; for, whereas Vajravarahi is actively associated in yabyum with her consort Heruka, or Samvara, an emanation of Akshobhya, Marichi always appears individually and her consort is Vairochana himself, and not any emanation of a Dhyani Buddha. Again Heruka rides a corpse, lying on its chest, and accordingly, such a vahana has been given to Vajravarahi but Marichi is never known to tread upon a corpse or even on the prostrate body of a man. The images of Vajravarahi always represent her as a single faced deity with an excrescence near the right ear, but Marichi even when represented with a single face is not known to have any excrescence on her face.

Vajravarahi according to the dhyana may have four arms, but Marichi must have either two, eight, ten or twelve arms, according to the Sadhana. Marichi is always said to reside in the womb of a chaitya, whereas Vajravarahi, being an abbess, may reside anywhere. The conception of Marichi has a greater antiquity than the conception of either Vajravarahi or Heruka. The union of Vajravarahi and Heruka is the subject matter of the Vajravarahi Tantra, but no Tantra is assigned to Marichi. Vajravarahi stands in ardhaparyanka in dancing attitude on a corpse, but Marichi stands almost always in the alidha attitude and moves in a chariot, but she is never in a dancing attitude. Vajravarahi has been called a Dakini (abbess) while Marichi has been conceived as a goddess.

Sixteen Sadhanas in the Sadhanamala [1] describe six distinct forms of Marichi. She may have, one, three, five or six faces and two, eight, ten or twelve arms. She is usually accompanied by her four attendants. She is recognised usually by her sow face and the seven pigs that run her chariot. The needle and string are her characteristic symbols, to sew up the mouths and eyes of the wicked.

Besides other attributes suggested for Marichi is the tarjanihasta, where the projected forefinger of the right hand points upwards. A person while threatening or admonishing another very often holds his hand in this position, and so there is a characteristic conformity between the actual practice and the artistic representation. In Vajrayana Sadhana Marichi and several other goddesses have the tarjani mudra.

In a sculpture of the goddess [2] Marichi discovered form Varanasi, she is standing in alidha position, like an archer with the right leg bent and the left out stretched. The garment on the left shoulder and the breast is but slightly indicated. The lower part of her body is clad with skirt held round the loins by a girdle. She has three faces. The left face is that of a boar with together with the vajra in her upper right hand accounts for Vajravarahi as well. Of the eight arms, the second right arm is missing. The third holds, what appears to be an arrow the shaft of which remains; and the fourth resting against the thigh. The attributes to the proper left are a bow, Ashoka flower, and a snare and tarjani mudra. Similar images of Marichi were also discovered from Nalanda, and other Buddhist sites in India.

Thus it is evident, in Buddhism too boar was venerated when a deity, with a boar face and the chariot driven by the boars, was introduced in the pantheon. Even today, Marichi is worshipped in Nepal as Vasundhara, and in Tibet under the name of Dorje Phagmo a literal translation of Vajravarahi.

In order to understand the plastic representation of Marichi, it should be remembered that she is the goddess of dawn, a personification of the rising sun. As such She is daily invoked by lamas when the sun's disc is first seen in the morning. For that reason she is regarded as the emanation of Amitabh, the Buddha of boundless light. As to Marichi's three faces, Foucher has pointed out the curious connection with certain Vishnu images met with in Kashmir, which likewise are three faced, that to the left being a boar's head (Vaikuntha form). Similar images are found in other parts of the western Himalayas. Sometimes the other side face is that of a lion. The two animal heads are believed to be referring to the boar and man-lion incarnations of Vishnu. It could be surmised that three faces of these deities were intended to signify the three phases of the sun, at dawn at noon and at dusk.

Whereas Marichi thus exhibits a close relationship with Vishnu, who from a Vedic Sun-god became the supreme deity of one of the great sects in India. Her image shows in one respect a remarkable affinity with representations of Surya. The seven boars on the pedestal correspond exactly with seven horses as seven days of the week. Evidently they are also meant to draw the chariot on which the goddess is supposed to stand and which in some cases is indicated by a wheel at each side of the pedestal. The cross-legged figure between Marichi's feet, whatever its name may be, clearly takes the place of Aruna, the charioteer of the Sun-god and may be thought to serve in the same manner with Marichi.

Notes and References

1. Bhattacharyya, B., Indian Buddhist Iconography, pp. 28ff.

2. ASIAR, 1903-04, p. 217.

XII

The boar in Jainism

The boar not only influenced the Brahmanical pantheon from quite an early date, but in Jainism too it enjoyed a place, though a subordinate one. The animal serves as a vehicle to the Jaina goddess Bala or Vijaya. [1] She is described in the Shvetambara books as a Yakshini riding over a peacock, and bearing four hands holding a citron, a spear, Bhusundi and lotus. [2] Canonically different account is given of Vijaya; in the Digambara sect, she is said to be riding a black boar, carrying the attributes of a conch, sword, disc and varada mudra:

जया देवी सुवर्णाभा कृष्ण शूकर वाहना ।

शडंखासि चक्र हस्तासौँ वरदा धर्मवत्सला ॥

Pratishthasarasamgraha (Arrah Ed.)

The above description reminds 3 us of a terracotta female figure of Isis, discovered from Ur in west Asia, seated on a boar, holding a harp or a ladder in her hands. The figure belongs to 300 B.C. This is quite important because the earliest specimen of boar in the Indian art has been known by about the same period.

Besides Garuda Yaksha in Jainism too is projected as riding a black boar, having four hands:

गरुडो नामतो यक्षः शान्तिनाथस्य कीर्तितः ।

वराह वाहन श्यामों वक़्वक्त चतुर्भज: ॥

Pratishthasarasamgraha (Arrah)

There is a Garuda 4 Yaksha on the southern face of a pillar near the entrance gate of the Deogarh Fort (Western), serving as an attendant to Shantinatha. He rides on a boar and holds a club rosary, citrus and snakes. All these agree mostly with description of texts.

In addition to the above, boar happens to be the symbol of Vimalanath [5] the thirteenth Jina of Jainism. Several images of the Jina were discovered from Sarnath, [6] and are also available in the State Museum, Lucknow; [7] Bateshwar and Agra. [8]

Notes and References

1. Bhattacharya, B.C., The Jain Iconography, Delhi 1974, p. 99.

2. Hema Chandra’s Kunthusvamin charitam:

तत्तीर्थ भूबढा देवी गौराड़ी केकिवाहना ।

विभ्राणा दक्षिणौ बाहु बीजपूरक शूलिनौ ॥

भुशुण्डी पडुजधृतौ विश्रति दक्षिणोत्तरी ।

सदा सनिहिता जज्ञे प्रभोः शासन देवता ॥

3. Nagar, S.L., The Universal Mother, fig.58.

4. Bhattacharya, B.C., op. cit p.78

5. Ibid, pp. 49-50.

6. Tiwari, Maruti Nandan Prasad, Jain Pratima Vijnana, (Hindi) pp. 106-07.

7. Ibid.

XIII

VARAHA TEMPLES

It has been discussed elsewhere in this work that the images of the Varaha form of Vishnu appeared in the Indian religious horizon as early as the 2nd century B.C. [1] and the iconographical features of the same were developed in subsequent period. Though there is ample evidence for veneration of Varaha during the Kushana period since (some sculptures belonging to this period have also come to light), but exclusive temples dedicated to the Varaha form of Vishnu could not be traced beyond the Gupta period. The independent temples exclusively dedicated to Varaha form of Vishnu are few and far between, though he is often found berthed in the niches inside and outside the Vaishnava temples. Still some of the early temples of Varaha are described here.

(i) Varaha temple, Eran

In this connection the temple at Eran could be cited as one of the first temples dedicated to Varaha. In the first year of the reign of Tormana, the first ruler of Hunas, the Gupta ruler had been supplanted temporarily. At Eran, there is a stone pillar inscription of the reign of Buddhagupta, which reads as follows:

"triumphant is the god, who had the form of a boar, who in the act of lifting up the earth (out of the ocean) caused the mountain to shake striking of his hard snout".

The identity of this god was made clear in line 7 of the inscription, where Dhanyavishnu [2] is reported to have erected the stone temple of the God Narayana, who has the form of a boar. It may be recalled here that in the Vajasneyi Samhita (37.5) and the Shatapatha Brahmana, Prajapati Brahma in the form of Enmsha or the boar has been described as having rescued the earth from deep waters. But it was only in the Gupta period that the boar was looked upon as an incarnation of Narayana. Though the Varaha temple initially constructed during the Gupta period at Eran is Currently in ruins, but the colossal Varaha image is still there, which has been described in detail elsewhere in this work.

(ii) Varaha temple, Ramtek

A colossal image of Zoomorphic [3] Varaha stands within the small four pillared mandapa raised over a Jagati which is restored in plain masonry. The Ruchaka pillars are decorated with paired lotus medallions with short octagonal and sixteen sided sections. The pillars have heavy bracket capitals which carry beams decorated with a thin row of padmapatras. The beams support a lantern ceiling composed of interesting Squares. The present roof of the mandapa was laid during the Bhonsle period, but enough remains to Show that the original ceiling was decorated with large lotus medallion, The present structure is topped by an amalaka recovered

from the site.

(iii) Varaha temple, Khajuraho

The Varaha temple at Khajuraho is a rectangular structure with its foundation on rock. It faces south-eastern part of the Lakshmana temple there. The structure has a pyramidal roof with receding tiers, which are lodged on a dozen pillars. There is a short frontal projection, supported on two other pillars, serving the purpose of the entrance to the shrine. The plan of the entire structure is quite simple and its size is modest. The shrine has no platform and is perched on a ten feet plinth of which the lower half is made of granite ashlars and the upper half of the sandstone. A flight of steps serve as an approach to the shrine. The steps are built in Sandstone and granite. This is a pavilion built in simple rectangular design and has a projection on the west. The whole structure is enclosed by a plain Parapet which was originally mounted on an ornate balustrade. The seat-slab of the parapet support the fourteen pillars. The shafts of the pillars are circular at the top, sixteen sided in the middle and octagonal at the base. Each one of them carry a plain circular capital surmounted by plain brackets. Over the brackets rests the beam of two plain offsets surmounted by an architrave with two offsets. The comers are filled with Kirttimukhas flanked by stenciled scrolls.

The colossal image of Varaha stands in the centre of the shrine. It is 8 feet 9 inches long and 5 feet 10 inches in width and is placed on a pedestal which is twelve inches in height. The image is a monolith, carved out of yellow- sand stone, having a fine finish and a glossy lustre. It is a beautifully modelled image of a boar, decorated all over with figures of various deities numbering 674. On the front of the muzzle between the two nostrils is depicted four armed Sarasvati seated in Jalitasana holding Vina in one pair of hands and a lotus and a book in the other.

Other deities depicted on the body of the boar include the nine Planets (Navagrahas), Dikpalas, Ganga, Yamuna, Siva, the eleven Rudras, numerous incarnations of Vishnu, besides Nagas, Vidyadharas and Gandharvas. Sheshanaga has been placed between the boar's feet, on the pedestal. Possibly there was the figure of a Garuda which held Sheshanaga in its month. The Earth-goddess Bhudevi is placed on the proper left of the boar. The tusk of the boar is broken as also the figure of Bhudevi.

***

Notes and References

1. Cf. The chapter on Vaikuntha form of Vishnu in this work.

2. CALL, I, (Gupta Inscriptions), Pp. 126.

XIV

Varahi

काम योगेश्वरी विद्धि क्रेधो माहश्वरी तथा ।

लेभस्तु वैष्णवी प्रोक्त ब्रद्मणी मद एव च ॥

मोह: स्वयंभू: कौमारी मात्सर्य चन्द्रजं विदुः ।

यमदण्डधरा देवी पैशुन्यं स्वमेव च ।

असूया च वराहाख्या इत्येता परिकीर्तिता: ॥

(Desires are controlled by Yogeshvari, anger by Maheshvari, greed by Vaishnavi, pride by Brahmani, state of confusion by Svayambhu Kaumari, jealously by the Shakti of Indra, bruteness by the goddess holding the staff and asuya by Varahi)

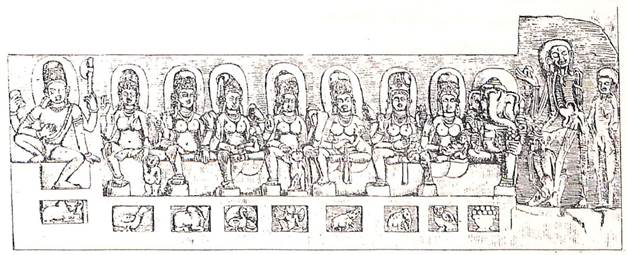

Varahi is believed to be the Shakti of Varaha, and one of the seven mothers-commonly known as Sapta-Matrikas. There are however Occasional deviations in the list of Matrikas with regard to their number and the order of their enumeration, usually they are seven, though eight or more can also be counted. The Skanda Purana, [1] the Devi Purana, [2] and the Brahmavaivarta Purana [3] mention more Matrikas, whereas the Devi Bhagavata [4] and the Linga Puranas [5] and other texts mention their number as eight only.

The genesis of the Sapta-Matrikas is described in detail in the Mahabharata, according to which during the Siva's fight with the Andhakasura, the Sapta- Matrikas were put into action in order to Stop every drop of the blood of the demon from falling on earth, which Could have created a powerful demon like him. All these Matrikas were engaged on the job. Mostly they are known as Brahmani, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda.

The warrior aspect of the goddess is amply projected in the Vamana Purana (30.21), wherein, she has been, called Varaha-rupini, fighting with the demons:

शत्तुया कुमारी कलिशेन चेन्द्री

तुण्डे चक्रेग वराह रूपिणी ।

The evolution of the Sapta-Matrikas in India, is connected with the cult of Mother Goddess in the country. The genesis of the cult could be traced back to a seal from the Indus valley civilization, wherein, seven female goddesses are shown standing, besides a tree, which represents a sort of a religious dance. The worship of these Matrikas is testified in a series of sculptures right from Kushana period [6] almost to the modern times.

The position of Varahi who happened to be one of the Sapta-Matrikas, has therefore to be discussed. The iconographical features of the goddess have been described in the text thus:-

कृष्ण वर्णा तु वाराही सूकरस्या महोदरी ।

वरदा दण्डिनी खड़े विशभ्रती दक्षिणे सदा ॥

खेट पाशाभयान्वासे सैव चापि लसदूभुजा ।

Vishnudharmottara

The forty-seventh folio of the Amishubhedagama describes the goddess thus:

वराह वकत्र सदृशा प्रल्याग्बुदु सन्निभा ।

करण्ड मुकयोपेता विद्रुभाभरणान्विता ॥

हलं च वरदं सव्ये वामे अभयशत्तिक्रे ।

कल्पद्गुम॑ समाश्रित्य गजध्वज सवाहिनीमू् ॥

वाराही चेति विक्षाता नाम्ना सर्व फ प्रदा ।

(Varahi has the face of a boar and the colour of a storm cloud. She wears on her head a karanda mukusa and is adorned with the ornaments made of corals. She weilds the hala, the Shakti, and is seated under a kalpaka tree. Elephant is her vahana and the emblem on the banner.

But the Vishnudharmottara states that she has a big belly and six hands in four of which she carries the danda, khadga, khetaka and pasha. The two remaining hands are held in abhaya and varada poses. The Purvakaranagama says that she carries the saranga-dhanus, the hala and musala as her weapons. She wears nupura-anklets on her legs:

इक पीताम्बरा शार्ज्ी सर्वसम्पत्क्की नृपाम् ।

पवित्रालज्जतोरस्का पादनूपुर संयुता ॥

सव्ये5भयं हल चैव मुसठ वरद मन्यके ।

वराह वकत्री वाराही यम भूषण भूषणी ॥

Brihat Samhita prescribes that the iconographical features of the Shaktis of the gods should be identical to those possessed by each one of them. Thus Varahi too has almost the same iconographical features as those of Varaha, which were duly translated into the Sculptural art in the country. It is not that she was represented only in the Sapta-matrika panels, alone, but on the contrary her individual images are also frequently met with, though in the matter of time these images do not compete with the presence of the goddess in the matrika panels.

Plate 7

One of the earliest sculptures of Varahi is preserved in the Shrinagar Museum. Wherein the four armed goddess is shown standing holding a chakra or a rosary, a club and possibly a damaru (?). The attribute of the fourth hand is not quite distinct. She wears beaded necklaces and wears a skirt with frills at the waist. The folds of the lower garment tends one to believe that the sculpture could have the influence of Gandhara art. She is standing in tribhanga posture with the right knee slightly bent. In the lower portion of the sculpture, there is a human face with a flat cap on its head. This figure could not be recognised.

The image of Varahi from the H.G. Museum, [7] Sagar, has a damaged face turned towards the right. She wears a karanda mukuta and is seated with the right leg stretching downwards and the left one folded and resting on a pedestal. The upper two hands hold some objects, while the lower ones fall down with Palms open possibly in varada mudra. She wears heavy ornaments.

A seventh century sculpture from Alampur Museum, [8] depicts the goddess Seated with the left leg folded resting on the pedestal and the right one hanging downwards. Her face of a boar is tilted towards the left. In her two right hands She holds a danda and an object, while the upper left hand holds a conch and the lower one is placed on her left thigh. She has beautiful hairdo and the usual Ornaments adorn her body. Her eyes are closed, as if in deep meditation.

Plate 8

An eighth century sculpture from Badoh in Vidisha district of Madhya Pradesn depicts the goddess having two arms. The face of the boar, which is tilted towards the left is damaged. The left hand too, which is apparently placed over the left thigh is also damaged, The right hand holds a danda. She is seated in the same manner as in the case of Alampur sculpture and is flanked by an attendant on each side. The Udaipur (Vidisha) sculpture depicts the goddess standing facing front and has two arms one of which is broken while the other holds a danda.

Plate 9

She wears a decorated karanda mukuta together with a vanamala – long garland of flowers, a waist-band and other ornaments. The figure is finely carved and projects two tusks.

The ninth century four-armed image of Varahi from Ashutosh Museum, depicts her seated over a double petalled lotus almost in the same fashion as the sculptures described above. In her two right hands, she holds a sword and a lotus, while the left hands hold a disc and an unidentifiable object. She wears a conical crown, bangles, necklace, ear-ornaments and anklets. She has a pot belly and her head is facing front. There is a small human figure flying at the pedestal.

Plate 10

A tenth century sculpture of the goddess from Simsthanatha Islands, depicts her pot-bellied, seated, facing front. She is two armed, and holds a dagger in the right hand and a bowl in the left. Though the face is that of a boar, but the ears are human, with round ear-ornaments. She wears a necklace which reaches her belly. Her head is decorated with beautiful hair style, which is damaged considerably.

Plate 11

A very interesting terracotta image of ten-armed Varahi with several human faces, besides that of a boar on the right is preserved in the Indian Museum, Calcutta. The two main hands are held in the front, while the others have been stretched on sides. She wears a crown on each head a necklace, other ornaments.

Plate 12

She is clad in vakala garment which is conspicuously projected by the skirt she wears. Of the attributes held in the left hands only the disc, the vajra and a bell can be recognised. The attributes of the right hands are not quite clear except the sword. Two demons are shown fleeing in opposite directions. The goddess stands in alidha posture placing her right foot over the demon.

Plate 13

A stone sculpture from Patan in Nepal depicts an eight-armed god seated over a pedestal. On his left thigh is seated the eight-armed Varahi, his consort.

Plate 14

Her right leg is folded, while the left one hangs down resting over the back of the seated buffalo whose head is turned upwards looking at the goddess. She wears a long garland of flowers. There is also a snake coiled in the front under the folded right leg of the god.

The thirteenth [9] century image of Varahi from Arsikere, Hassan district of Karnataka is a beautiful piece of sculpture showing the goddess standing, thickly ornamented holding shamkha, chakra, gada and the lotus in her four hands. The head, with a halo at the back wears a decorated karanda mukuta. She is flanked by two miniature temples.

The image of Varahi [10] from Birla Museum, Bhopal is quite unique because in this the goddess has been depicted holding a fish. She is seated in Jalitasana having four arms, holding a khadga, khetaka, skull-cup and a fish.

An image [11] of Varahi, the consort of the boar incarnation of Vishnu was discovered from Jajpur in Orissa. She is shown as seated in an easy posture with right leg pendant and Testing on a buffalo on the pedestal below. She has three eyes and three Tows of curly hair. She wears the usual ornaments and a sari. She holds a child in her left arm, who is seated on her left thigh.

Plate 52, 54

There is an interesting image of a four armed goddess from Jageshwar-Almora, seated over a Mahisha-buffalo. She wears a jata-mukuta over her human head, while the head of a boar or the one resembling to that of a horse (?) emerges to the left side of the neck. In her four hands she holds a cup, a bell, a fish and a cowrie. Of these attributes of cowrie and the cup are quite distinct but the other two could be doubtful. The lower left hand holds an object which looks like a fish. It may be recalled here that the image of Varahi in the Birla Museum, Bhopal, also is depicted holding a fish, as discussed earlier. A doubt could be expressed about the attribute identified as bell held in the upper left hand of the goddess which looks like a scrole. This doubt would be fully cleared when viewed in comparison with the similar attribute held in the upper left hands of Mahishasuramardini and Maheshvari in the sculptures from the same site- The sculpture has been believed to be of Varahi by scholars, but the animal head projected besides the human head looks more like that of a horse, rather than that of a boar. The sculptor possibly intended to carve the head of a bow but could not execute it to resemble it minutely.

For the identification of this sculpture (P1.52) it may also be necessary to examine this buffalo as the vehicle of Varahi. The buffalo appears as the vehicle of the g0ddess in a sculpture from Jaipur in Orissa as pointed out earlier. Further J.N, Banerjee in his celebrated work, has brought our the following iconographical features of Varahi on the basis of some seals from Nalanda [12]:

“She is most probably Durga-sinthavahini: She appears thus on another monastic sealing (5.9,75), three of her hands holding a mace (gada), a sword (khadga) and the lotus Stalk, the animal below her looking like a buffalo. Buffalo is the usual mount of Yama, the god of death, as well as that of Varahi, one of the Sapta-Matrikas, but here the goddess does not look like her. Another buffalo-riding four-armed Devi appears on a sealing (S.I.547), with a sword and a wheel (chakra) in her upper right hands and a trident (trishula ) in her lower right, the object in the lower left being indistinct. She also does not look like Varahi and the objects held in her hand are indicative of cult amalgam”.

The above passage also establishes that Varahi has at times, the buffalo as a vehicle. The Rupamandana also prescribes the buffalo as the vehicle of Varahi:

वाराहा तु प्रवक्षामि माहिषी ऋमस्थितम् ।

वरहसदृशं घण्टनाद चामर धारिणी ॥

While the bell, the cup, and the cowrie are the attributes commonly found depicted in the images of Varahi, but the fish is not quite common. In this connection O.P. Mishra [13] informs as follows:-

“Dr. Agrawala (R.C.) has reported that the presence of a fish in one of the hands of these two faces is probably some tantric trait. This needs further confirmation from literary data. Recently Dr. Agrawala noticed a rare image in Varahi from Jageshwar which is datable to the 8th-9th century A.D. Here we find two faced Varahi, which is quite unusual as one of the faces is human while the other is that of a boar. No other image of this type has appeared to have been noticed so far”.

The holding of fish in the hand of Varahi is quite unusual, and it has not been possible to explain it with reference to the provision of the texts, though other symbols would lead one to believe it to be the image of Varahi chiselled under the influence of some local traditions of the contemporary period. Such local variations are commonly found in sculptures of deities of different periods. A glaring example of this is that sometimes the Marika panels depict the goddesses in complete human form, and the identification of each one of them is possible with reference to the figure of the vahana etc. carved over the pedestal below each one of them. An illustration of this fact is available in the Sapta-matrika panel from Ellora, where the vahana of each one of the goddesses is carved below the seat of each one of them, But in the case of Varahi, in the same panel, an exception has been made. Under the seat of Varahi who appears in complete human form, the figure of a boar has been carved instead of the mount which should be a buffalo or a Garuda. But since Garuda is shown as a vehicle of Vaishnavi, the only alternative left with the artist was to carve the figure of the boar under the pedestal in order to suggest the goddess depicted was Varahi.

***

Notes and References

1. Skanda Purana, Kashi Khanda, 83.33, of the Uttarardha.

2. Devi Purana, CL. 87.

3. Brahmavaivarta Purana, Prakrti Khanda, 64.87-88.

4. Devi Bhagavata Purana, 82.96.

5. Linga Purina, (Purvardha) 82.96. od

6. Misra, OP., in his work on Iconography of the Sapta-matrikas, pp. 100-101, has furnished the list of Varahi panels, as under:

Place / Museum / Period

(1). Hinglajgarh / Central Museum, Indore / 4th century A.D.

(2). Sagar / H.G. Museum, Sagar / -do-

(3). Jogeshwar, U.P. / ... / 6th-7th century A.D.

(4). Mathura / Mathura Museum / -do-

(5). ... / British Museum, London / Late Gupta period

(6). Alampur / Alampur Museum, (Andhra Pradesh) / 7th century A.D.

(7). Jogeshwar / ... / 8th-9th century A.D.

(8). Lolkhedi (Mandasor) / Local Museum / 9th century A.D.

(9). ... / Chandigarh Museum / -do-

(10). Badoh (Vidisha) / Central Museum, Gwalior / 10th century A.D.

(11). Suvasara (Mandasor) / Private collection / -do-

(12). Asapari (Raisen) / Birla Museum, Bhopal / 10th century A.D.

(13). Terhi (Shivpuri) / A.S.I. Collection / 10th-11th century A.D.

(14). Bheraghat Jabalpur / Bheraghat temple / -do-

(15). Begali (Bellary-Mysore) / ... / 11th century A.D.

(16). ... /Birla Museum, Bhopal / -do-

(17). ... / Khajuraho Museum / -do-

(18). Arasikere (Hassan, Karnataka) / 1220 A.D.

7. Misra, O.P., op.cit., p.94, P1.64.

8. Ibid, p.95, p1.65.

9. Ibid, pp.98.99.

10. Ibid, p. 99.

11. ASIAR, 1925-26, p.34.

12. Banerjea, J.N., op.cit, p. 186.

13. Misra, O.P., op.cit, p. 94.

XV

Epilogue

ऐतत्ते कथयिष्यामि पुराणं ब्रह्मसम्मितम् |

महा वराह चरितं कृष्णस्याद्भुतकर्मण: ॥

The boar as a wild animal has been known the world over from time immemorial. The evidence relating to the presence of wild boar is available from the pre- historic rock paintings in several countries including India. The most important evidence of the boar as a wild animal in India is available in the rock shelters of Bhimbetka near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh. Not only that, the boar is found present in the Indus Valley culture as well, because a number of seals from Mohenjodaro depict the wild boar in one form or the other. Up to that stage the boar was possibly meant for hunting purposes alone and no traces of its having acquired a divine status are forthcoming.

In the Rigvedic and other texts, the boar can be classified under two broad divisions. In one the slaying of boar is related and in the other the lifting of the earth is mentioned. These references belong to two different myths. Possibly in the earlier myth, the boar was only treated as a wild animal, whereas in the other one, some sort of divinity was associated with it when the feat of the rescue of the earth from the deep waters Is said to have been accomplished by him. However, the earliest reference to Varaha's association with the earth in clear terms is found in the Bhumi-Sukta of Atharvaveda. In the later Samhitas and Brahmanas there are some versions of the myth in which Varaha appears as a diver who plunged into the deep waters.

There are, in fact, several stages covering the long period from the Vedas to the cosmogonical sections of the Puranas, dealing with the story of boar. In the first phase, the boar dives into the water to fetch the earth from out of the deep waters. There are some variations in the accounts concerning the Varaha, in different texts. Besides there is also a controversy as to who incarnated as boar – Brahma/Prajapati or Vishnu.

In the earlier editions of the Ramayana of Valmiki (2.102.2-4) it was Prajapati Brahma who became a boar and lifted the earth. This agrees with the version of the story available in earlier texts. In some Purana texts too, the Varaha is the form of Brahma who is later identified with Narayana. In the still later stage represented by the Vayu, Brahmanda, Vishnu and the Kurma Puranas, Vishnu takes the role of Brahma in assuming the Varaha form. But in the comparatively later versions of the Ramayana and the Puranas, the feat was attributed to Vishnu as Narayana.

Varaha even after attaining religious sanctity as one of the incarnations of Vishnu emerged in the Indian plastic art quite late. One of the earliest sculptures with the projection of Varaha, was possibly discovered for Bhita and is preserved in the Lucknow Museum. This sculpture has been dated back to the 2nd-1st century B.C. wherein the boar appears in complete animal form and is lodged before the human figure which is intended to represent Vishnu. No image of the composite form of Varaha prior to this date could be noticed.

However, after his attaining the religious sanctity, Varaha was portrayed in Indian plastic art in animal as well as in composite form having the head of a boar fixed over the human trunk. The images in animal form have been discovered from Earan, Apasad (Gaya), Khajuraho, Jhalawar and the one from central India, currently preserved in the Nagpur Museum.

In a majority of the cases when Varaha is projected in composite form, the boar face is turned towards the left, with the Earth-goddess seated more often than not over the upper left elbow. The left side, in such cases, has its own significance, because, earth in some text is conceived to be the consort of Varaha form of Vishnu and demon Naraka was born as a result of this contact between then. Thus to lodge her on the left side of the god would be quite appropriate in the true Indian traditions. There are however, exceptions to this as well, in as much as in some cases the face of Varaha is found turned towards the right and the Earth-goddess is found lodged to the right. In the sculptures from Mahabalipuram and Namakkal, Varaha is shown turning the face to the right with the Earth-goddess perched over the elbow of the right hand. Varaha has also been shown as two-armed, four-armed even multi-armed. Interestingly, he is shown at early stages without a head-dress, but in the later period his head is decorated with various type of mukutas or well-arranged locks of hair in the form of jata mukuta or those let loose, falling on to the shoulders.

There has been another tradition, that while depicting Varaha in complete animal form, the figures of various divinities, saints and sages were carved over the entire body of the boar as would be evident from the Varaha sculpture from Khajuraho, Apasad and Jhalawar. As to the depiction of the Earth-goddess in relation to Varaha, it may be pointed out that during the Kushana period, as would be evident from the sculpture from Mathura, she was found seated over the shoulder of Varaha. In the early Gupta period she was shown standing over a lotus stalk, as would be evident from her projection in the Udaigiri cave sculpture. Quite often she was shown perched over the upper left elbow of the god, but occasionally she was placed over the right elbow as well as in the case of Mahabalipuram and Namakkal. In a nineteenth century Pahari painting, instead of being projected in human form, earth has been represented as mountain placed over the snout of the Varaha. In a few cases she has been shown as a youthful female seated over the snout of the boar.

Adishesha has been another important constituent of Varaha sculptures. He is usually depicted with a single, three or five snake hoods in a composite form with upper half being human and the rest of the snake. Often he appears with folded hands with his consort placed in similar position in adoration of the god.

Hiranyaksha has been another constituent of the Varaha episode, who is said to have made the Earth-goddess captive and to rescue her, Varaha ha d to subjugate the demon. This demon is found trampled up by the god in a number of sculptures illustrating this work.

An important aspect of the Varaha episode had been that it influenced monarchy immensely and many rulers after conquering one territory or the other, symbolized or equated their victory with Varaha who had rescued the earth. Some of the rulers patronised Varaha as royal insignia or emblem and during the medieval period Mihirbhoja even issued Varaha coins and adopted the boar as royal emblem.

There is a school of thought which identifies Varaha with rhinoceros. Umakant Shah (JOIB Vol. 8,-1959, pp. 41-70) while dealing with Vriksha Kapi in Rigveda, has expressed his doubts in this connection. According to him the trikunda on the body of Varaha makes one believe that they point to a rhinoceros rather than a boar. He further believes that “it is the rhinoceros that signifies the description of the Mahabharata since its body is stated to look uneven due to thick folds, and from the mouth to the tail, the surface of the body of the rhinoceros seems to have three elevations. Besides it is the rhinoceros that can be really described as ekashringa and not the boar”. But this theory has been strongly contested by Maheshwari Prasad, who fails to accept the identification of rhinoceros for boar mainly because of its having been described as ekashringa. There are several references in the texts where even fish is supposed to have a single horn, whereas ordinarily the fish has no horns. Moreover, the texts besides Varaha have also described this form of Vishnu as Sukara which unambiguously stands for a boar and not the rhinoceros. It is not that rhinoceros was unknown to the ancient world. It was called Ganda or Gandaka in the texts and as such to assume Varaha as rhinoceros could not possibly be justified. Having discussed the various aspects of Varaha, we may conclude:

त्रिविक्रमायामितविक्रमाय महावराहाय सुरोत्तमाय ।

श्री शार्ज्न चक्रसि गदा धराय नमोड5स्तु ते देववर प्रसीद ॥

Matsya Purana, 248.12

(I salute you, O, the most valiant one, in all three realms, the most illustrious Maha Varaha, the most powerful of all the Devas, the one armed with sword, quoit and club etc.)

THE AUTHOR

The author having served in the curatorial capacity in the Central Asian Antiquities Museum, New Delhi, the Nalanda Museum and Archaeological Section of the Indian Museum, Calcutta, was credited with the scientific documentation of over fifty thousand antiquities comprising sculptures, bronzes, terracottas, beads, seals and scalings, wood work, paintings, textiles and Pearce collection of Gems, ranging from the earliest times to the late medieval period.

Besides publishing bilingually, three publications of the Archaeological Survey of India, he has also brought out the works entitled: (1) Mahishasuramardini in Indian Art, (2) The Universal Mother, (3) The Composite Deities in Indian Art, (4) Garuda the Celestial Bird, (5) The Indian Monoliths, (6) The Cult of Vinayaka, (7) Jatakas in Indian Art, (8) The Temples of Himachal Pradesh. He was awarded a fellowship by the Indian Council of Historical Research, in 1987, for his last mentioned work.

His other works in press include:

(i) Shiva in Indian Art, Thought and Literature,

(ii) Mahishasuramardini (Hindi).

In addition to above, his works entitled (1) The Svastika, (2) The Cult of Surya in India are in the pipeline.