42. Four-armed Varaha, Chittorgarh, 12th century A.D.

43. Four-armed Varaha, Gauhati Museum, 12th century A.D.

44. Four-armed Varaha, Pushpagiri, 14th century A.D.

45. Four-armed Varaha, Hyderabad, 14th century A.D.

46. Four-armed Varaha, Chamba Museum, 14th century A.D.

47. Four-armed Varaha, Channakeshvara temple, Belur, 14th century A.D.

48. Four-armed Varaha, Rani Pokhari, Nepal, 19th century A.D.

49. Four-armed Varaha, Patan, Nepal, 19th century A.D.

50. Six-headed Varaha, with Earth-goddess, Patan, Nepal, 19th century A.D.

51. Pahari Chamba painting, 19th century A.D.

52. Varahi, Jogeshwar, 9th century A.D.

53. Mahishasuramardini, Jageshwar, 9th century A.D.

54. Maheshwari, Jageshwar, 9th century A.D.

Notes and References

1. Singh, S.B., Brahmanical Icons in Northern India, p.77, fig.35.

2. Smith, V.A., Catalogue of Coins in the India Museum, Calcutta, pp.241-42, p1. XXV, 18.

3. Devi Mahatmya, 5.51; Matsya Purana, 247.50.

4. ASIAR, 1908-09, p.9.

5. Singh, S.B., op.cit, p.73.

6. Gopinatha Rao, T.A., Elements of Hindu Iconography, Part I, Vol. N, pp.140-41, fig. XXXVII

7. Ibid., pp. 141 ff, pl. XXXVIII(2).

8. Deva, K., Images of Nepal, p.20, pl. 33(B).

9. LA., 1955-56, p.29, pl. XLVII(B).

10. Champakalakshmi, R., Vaishnava Iconography in the Tamil Country, p.85, fig.16.

11. Ibid, p.85.

12. ASIAR, 1908-09, p.106.

13. Champakalakshmi, R., op.cit, p.88, fig.20.

14. Singh, S.B., op.cit, p.72.

15. Bhattashali, N.K. Iconography of Buddhist and Brahmanical Sculptures in Dhaka Museum, pp.103-104, pl. XXXVI, 1&2.

16. Champakalakshmi, R., op. cit, p.89, fig. 21.

17. Smith, V.A., op. cit, pp.241-42.

18. Gopinatha Rao, T.A., op.cit, pp.14243, p1.XL.

19. ASIAR, 1912-13, p.137, p1.LXXIX.

20. Mastharamaiah, B., The Temples of Mukhalirigam, pp. 81-82.

21. Gopinatha Rao, T.A., op. cit, pp. 143-44, p1.XLl.

22. Singh, S.B., op. cit, p.83.

23. Pal Pratapaditya, Bronzes of Kashmir, p.71.

VII

The Epigraphs,

Seals and Numismatics

भुवः प्रेम परिषूंग पुलकांकि लबावहे |

नमो वाराह वपुषे श्री वैभववपुषे लिषे ॥

E.1.VIII, p.309

The epigraphical records in the Country have their own importance in the matter of the study of ancient Indian history, culture and civilization. According to D.C. Sarkar, [1] "Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions and ‘inscription’ literally means any writing engraved on some object. In India, rocks as well as lithic, metallic, earthen or wooden pillars, tablets, plates and pots, as also bricks, shells, ivory plaques and other objects were generally used for incising inscriptions. Often writing in relief such as we find in the legends on coins and seals which are usually produced out of moulds or dies, and also records on painted cave walls Or written in ink on wooden tablets, are regarded inscriptions, although these writings are not actually engraved. As is usually the case with inscriptions in the Perso-Arabic script, the letters of certain late medieval records in the indigenous Indian alphabets are generally not engraved but are formed by scooping out the space around them”.

The same scholar further [2] goes on to testify that, “Excluding coins, and seals bearing the legends which are not inscriptions in the true sense of the term, the largest number of Indian epigraphic records belong to the category of stone inscriptions. Most of the early prashastis are incised on stone-rocks, tablets or pillars, though in the later period, they were also incorporated in royal charters engraved on copper plates”.

These epigraphs occasionally refer to the boar form of Vishnu in more than one way. It may not, however, be possible to produce all the available evidence in this regard, due to obvious reasons, but an attempt has been made to highlight some selected ones for the purpose of reference. An inscription [3] of Samudragupta (A.D. 350) on a square red stone block was found from the old Varaha temple at Eran, in which there is the writing of Tormana. The original stone is now in the Indian Museum, Calcutta. Probably it refers to the erection of a temple of the Boar incarnation of Vishnu.

The inscription is engraved on the chest of the colossal red stone statue of the boar about eleven feet in height, representing Lord Vishnu in his incarnation as Varaha that stands facing east, in the portico of an ancient temple. The boar is covered all over with elaborate sculptures, chiefly of sages, clinging to the mane and bristle. It has the earth represented as a female, hanging on in accordance with the legend, to its right hand tusk; and over its shoulders there is a small four sided shrine, with a sitting figure in each face of it.

The inscription refers itself to the reign of Tormana. It is dated in words in the first year of his reign, without reference to an era; and on the tenth day, without any specification of the fortnight, of the mouth of Phalguna (February - March). The object of the inscription is to record the building of the temple, in which the boar stands, by Dhanya Vishnu, the younger brother of the deceased brother Matri Vishnu.

In the Damodarpur copper plate inscription of Buddhagupta, [4] it is intended to highlight the purchase of land to erect on it, two shrines and two store-rooms of the primeval gods Kokamukha-Svamin and Shveta-Varaha Svamin, to whom four and seven kulyavapas respectively had already been donated by the donor on the table land of the Himalayas in the village of Donga.

Kokamukha Svamin and Shveta Varaha-Svamin are undoubtedly the forms of Vishnu but their actual place of location is not known. R.G. Basak [5] suspects that the first of these was connected with Kokamukha tirtha mentioned in the Harivamsha, Mahabharata [6] and Varaha Purana. [7] J.C. Ghosh is more positive on this point and locates it in the region where flow the rivers Kaushiki, Koka and Trisrotas as mentioned in Chapter 140 of the Varaha Purana and answering to the modem Kosi, Kankai and Tista in Northern Bengal. Anybody who reads this chapter carefully will be convinced that Koka emerges from the Himalayas. This agrees with the fact that the two gods mentioned in Damodar copper-plate of Buddhagupta were on the table-land of the Himalayas. The Varaha Purana (140-68) speaks of a sacred place called Damshtra Kura just where the Koka emerges. This seems to be the location of Kokamukhasvamin. In fact the actual name Kokamukha occurs twice in the Varaha Purana (122.19,22 and 140.4). The same Purana (140.24) mentions Vishnusaras [8] as a place where Varaha pulled out the earth with one stroke of his tusk. This appears to be the location of Shveta-Varaha Svamin. This perhaps explains why the earth has been described in this inscription as linga-kshoni, the Subtle Earth. From the names of the rivers Kaushiki and Koka and Trisrotas, that is, the Sun Kosi, Kankai and Tista, it is clear that the Shrines of these gods were situated somewhere in Darjeeling and Sikkim and as such it is no wonder if one image of the boar incarnation was called Shvetambara Svamin. Possibly the images of these gods and the earth were the natural formations of rocks. This agrees with the fact that the gods have been called adya or primeval in line 7 and the earth described linga-kshoni in line 8 of the said inscription. In the Pallava and Pandya [9] inscriptions, no direct reference to the Varaha form of Vishnu is found. The concepts however, seems to be alluded to in the Kashakkudi plates of Nandivarman II. The idea embodied in these lines is that the Pallava race resembled an incarnation of Vishnu in the Conquest of the world, thus indicating the Varaha in incarnation. One of the panel depicting historical events in the Vaikuntha Perumal temple in Kanchipuram, gives shape to this idea as it contains a relief of the Varaha form lifting the earth similar to the one found at Mahabalipuram Varaha mandapa.

The Chalukyas of Badami, [10] who adopted the boar as their emblem, invariably invoked Vishnu in the form of the boar in all their copper plate grants. The Nausori Plates of Sryasraya Shiladitya dated to Chedi era 421 (A.D. 671) opens with an invocation to the boar incarnation and gives the following description of the form:-

“Hail! Victorious is the body of Vishnu manifested in the form of a boar on whose uplifted right tusk rests the world and who has agitated the ocean." An inscription in the Gupta temple, Deogarh, [11] in Madhya Pradesh, refers to the creation of a temple of god Nrihari by Adityasena, coming from the Chola metropolis (चोलपुरादू-उपेत्य) accompanied by his wife Kashadevi (i.e. Konadevi), and also installation of the image of Varaha.

The Varaha form of Vishnu is often mentioned in the inscriptions of Chola and Pandya periods. This incarnation is described in an inscription of Rajendra II [12] (dated in the third regnal year), from the Saundararaja Perumal temple in Somamangalam in Chengalpattu district. The god here is stated to have assumed the Varaha form and rescued the earth goddess.

An inscription of the time of Someshvara-I, [13] Shaka Samvat 981, corresponding to A.D. 1060, invokes the Varaha incarnation of Vishnu, who, while stirring up the ocean rescued the Earth-goddess resting on the tip of his lofty tusk.

The Madanpur inscription [14] of the reign of Kanahara, belonging to A.D. 1246, invokes Varaha incarnation of Vishnu in its verse 2, who took in sport, the form of the boar on whose tusk tip dwells the constant mass of his peculiar radiance and with the design of dissipating the guilt arising out of the touch of Hiranyaksha’s efforts as it were an assured bath in the flood of the celestial Ganga.

स्थिरायद्दंट्राग्रे निवस्ति तदीय, द्युतिचयो हिरण्याक्ष

स्पर्शप्रभवदुरिता ध्वंसनधिया

विच॑ (य) द् गंगा पूरे प्रवं-इव विगाहमूविदधति (ते) हरिः

क्रेध क्रीड़ा: स जयति यति स्तुत्य विभवः ॥२॥

The Shrirangam plates of Mummadi Nayaka [15] of Shaka Samvat 1280, invoke Shveta-Varaha, as the third incarnation of Vishnu. It could, however, be stated here that the texts rarely define, Varaha in white complexion, who is usually described as of the colour of dark clouds. But here the description as Shveta-Varaha is therefore quite unusual.

Madras Museum plates of Shrigiribhupala [16] (Shaka Samvata - 1346) in verse 3, offers salutation to the effulgence, whose form is that of a boar, whose arm bristled with pleasure at the loving embrace of earth, (when he brought her up from the deep sea waters).

The Dandapalla plates of Vijaya Bhute [17] of Shaka Samvata 1332, (A.D. 1410) invokes the glorious Varaha (in verse 2) who bore aloft the delighted earth sunk in deep waters of the ocean.

The Shrishailam plates of Virupaksha, [18] of Shaka Samvata 1388, corresponding to A.D. 1468, adores the Varahamurti form of Vishnu in verse 3 of the epigraph.

The Bevinhalli grant of Sadasena Raya [19] of Saka Samvata 1473 invokes the blessings of the boar incarnation of Vishnu. The Vellangudi plates of Venkatapatideva Maharaja-I [20] of Shaka Samvat 1520, corresponding to A.D. 1590 offers adoration to the boar incarnation of Vishnu. The Penuguluru grant [21] of Tirumala belonging to Shaka Samvat 1493 (A.D. 1572) invokes Varaha, besides other deities like Ganapati and Shiva in the third verse of the epigraph.

Seals and Sealings

As already pointed out, the original concept of Varaha incarnation lies in the Vedic literature followed by the Brahmanas and other subsequent literature. But the representation of the boar incarnation of Vishnu, though evolved, evidently during the Sunga-Kushana period, became popular in the sculptural art of the Gupta period, wherein both the theriomorphic and therioanthrophic types occur frequently. The Paramabhagavata, Imperial Gupta kings favoured this incarnation because it could also symbolise their saving the country from depredations of the foreign Sakas and Hunas.

Several seals from Rajghat bear the figure of boar and the legend Rasikasya in Gupta character. [22] The animal is also found to occur on the Basarh sealings. Boar figures also occur on number 18 in Bloch's [23] list and numbers [24] 54, 325 [25] and 341 [26] in Spooner's list in Basarh seals. Seal No. 54 from Basarh is a unique example and a very handsome one without a legend. It has a finely executed figure of a boar recumbent to left as its device. In artistic excellence the seal is unusual. Similar type of seals are also found from Sunet [27] and Lucknow. [28] In both the cases a running boar is depicted with an inscription below the figure.

A Still more interesting and definite representation occurs over a Rajghat sealing currently preserved in the Allahabad Museum (No.110) showing Varaha lifting the Earth-goddess. Varaha here is shown in composite form with the head of a boar fixed over a human body.

Seal No. 341 is also beautiful. It is a thick lump of a very pale clay, very concave On the reverse. The impression is that of a square oval seal with double hair-line border. There could have been a legend there, which is doubtful. The device is exceptionally interesting from the artistic point of view. It shows the figure of a spirited horse galloping to left with the well-drawn figure of a bar running to right in the background.

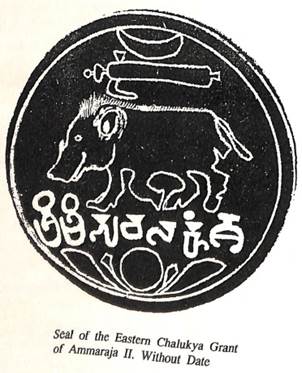

Dayyamdinne plates of Vinayaditya-Satyashraya [29] of A.D. 692, are joined together with a ring. The ends of the ring are fixed to the bottom of an almost circular seal, one inch in diameter. It bears on its countersunk space; the crude figure of a standing boar facing the proper right.

An oval seal [30] from Basarh depicts a boar, a conch-shell on each side, besides the symbols of sun and moon and a legend below.

Another sealing [31] from the same site is a thick lump of very pale clay and concave on the reverse. The impression is that of a square oval seal with double hair-line border. The device is quite interesting from the artistic point of view. It shows the figure of a spirited horse galloping to the left with the well-drawn figure of a boar running to the right in the foreground.

The Arumbaka plates of Badapa [32] discovered from Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh, have a massive seal fixed to the ring binding the plates. On its surface the figure of the crescent is cut in relief at the top and the ankusha in horizontal position placed below it, with a legend. Below the legend is the figure of a boar standing on a lotus. The figure of sun is cut towards the proper left of the seal, near the head of the boar.

The seal [33] attached to the ring of the copper plates from Shripundi of Tala II, have almost identical features with the figure of a boar.

The Tiruvalangadu copper plates of Rajendra Chola [34] have a boar on the seal, which has been interpreted to mean the king's conquest of both Eastern and Western Chalukyas, whose crest was a boar.

The boar also appears on a seal attached to the ring binding the copper plate grants of Payalabanda Krishnadeva, [35] which belongs to A.D. 1524.

Five Kandukuru plates [36] of Venkatapatideva dating back to A.D. 1613, were discovered from Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. They have raised rims and curved tops, with a ring hole bored in the middle. The ring which is circular in shape has a sliding circular seal. On this seal is represented in high relief a boar advancing to the proper left, and a dagger pointing downwards; both cut up a horizontal double line supported by a vertical line in the centre. Above the boar, are the figures of sun and crescent.

Varaha in Coins

While tracing the presence of Varaha in the Indian numismatics, it may be stated that it is the Earth-goddess who appears in the coins of ancient India. Allan has tried to trace the presence of the Bhudevi, in the coins of Bhumimitra, though he is not quite sure of the same. He observes 37 in this connection thus:

“Bhumimitra has a deity standing facing on a platform between two pillars each with a three cross-bars at the top. His attitude is similar to that of Agni, but his hair is represented by five snakes (nagas). He holds a mace in his hands. One would expect the personification of the Earth-goddess Bhurrii but, as the figure is male, it is probably the king of nagas representing the earth”.

Foucher has identified the figure with Adinaga, the presiding deity of Ahichchhatra, the capital of Panchala. This observation is based on the comparative study of the devices on the reverse of the coins of Bhumimitra and Agnimitra, the Panchala rulers. [38]

However in the gold coins of the kings of Nala dynasty of Central India, the words ‘Shri-Varaharaja’ [39] and ‘Shri Varaha’ are found embossed over the obverse of the coins. Though these legends ostensibly refer to the ruler of the dynasty in the 5th century A.D., but the second one ‘Shri Varaha’ could possibly be interpreted to mean Varaha form of Vishnu as well.

Two inscriptions from Shergaddh [40] belonging to A.D 1082 testify that Devasvamin prescribed monthly payment of two varahas (equivalent to old 3½ rupees) to be made on the occasion of Samkranti. The object of donation is not stated; it was probably a contribution to the general funds of the temple Varahas are obviously silver coins issued by Pratihara King Bhoja, and probably some of his successors as well, which have on one side the image of a boar. These coins were about 60 grains in weight. The inscription testifies the use of Varaha coins thus:

तथा मासवारके संक्रांती वराह (ही) ही प्रदत्तो आचंद्रवः यावत् ।

V.S. Agrawala too has published the figure of Adi-Varaha 41 on the coin s of Mihir Bhoja, belonging to A.D. 836-885.

***

Notes and References

1. Sarcar, D., Indian Epigraphy, p.1.

2. Ibid, p.5.

3. C.I.I., Inscriptions of Early Gupta Kings, Vol.II, (Revised) p.221

4. Ibid. p.221.

5. EI. XV, p.140, Note 3.

6. Mahabharata, 3.84.159.