The episode and its Salient features

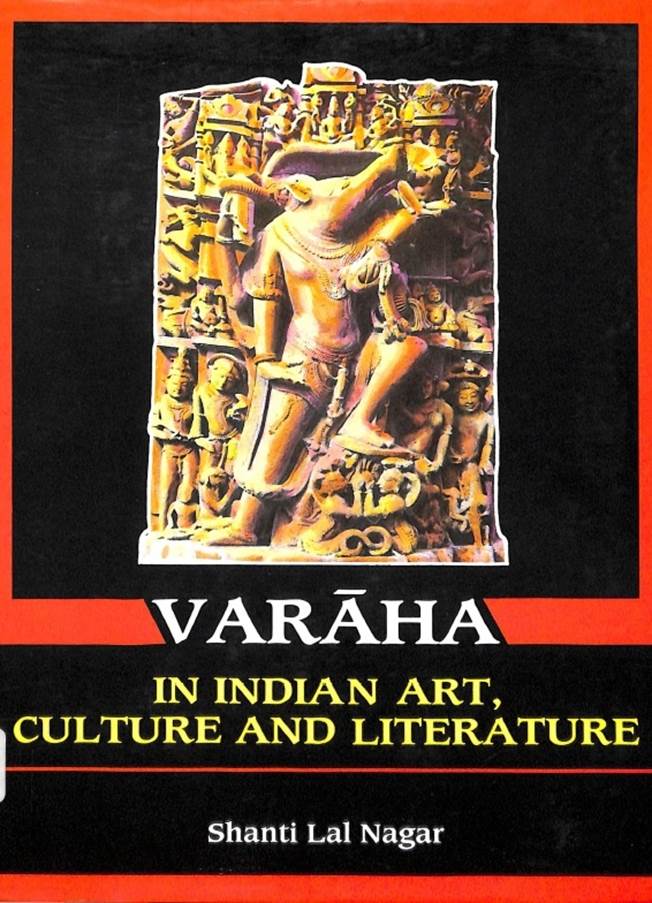

Lord Varaha

In Indian Art, Culture

And Literature

Shanti Lal Nagar

ARYAN BOOKS INTERNATIONAL

NEW DELHI

Printed in India

1993

***

The boar, a wild animal of considerable strength and speed, has been known the world over from the time immemorial, as evidenced from the ancient texts as well as archaeological sources. Initially it was a hunting animal possibly meant for human consumption, but gradually it entered the con temporary religious thought in various countries of the globe. The Indian evidence portraying reverence to the animal is comparatively later than that of the other countries of the world. As for example the animal is found depicted in the coins and legends of Greek, Crete and Rome etc, centuries before the Christian era, which was followed in the later period.

In the Indian context, the animal, though occasionally appears in the Vedic and post-Vedic literature, but its reverence achieved a great boost after its association with the incarnation of Vishnu, a strong and powerful Brahmanical god. In this form the boar, it is stated, rescued the earth-goddess submerged under the deep sea-waters. The reasons for the drowning of the Earth have been quite convincingly given in the texts. The Mahabharata is quite vocal in this regard, wherein, it is stated that the earth was submerged in water because of its overpopulation.

The salient features of the episode are (i) the Deluge, (ii) the Earth, (iii) the Demon Hiranyaksha, besides the boar. With the passage of time the theme of the rescue of the earth became symbolical with the rulers of the country, who after having conquered a territory or overthrowing the foreign domination, equated the event with the rescue of the earth by the boar incarnation of Vishnu. Such events were celebrated by erecting an image or a temple of the god.

The present work aims at highlighting the various aspects of Varaha form of Vishnu, in the background of the literary as well as the archaeological evidence, available in the country.

***

Preface

अयं मत्यो5भवत् पूर्व पुनः कूर्म्मस्वरूपवान् ।

वराहश्चाभवद् देवों नरसिहस्ततोऽभवत् ॥

वामनस्तु ततो जातो जामदग्न्यों महाबल: ।

पुनर्दाशरथि भूत्रवा वासुदेवः पुनर्बभी ॥

बुद्धो भूत्वाजनं हयेष मोहयाभास पार्थिव ।

सपलान् दस्यवो म्लेच्छान् पुनर्हत्वा महीममिमाम् ।

प्रकृतिस््थां चकरायं स एष भगवान् हरि ।

(The Lord first took to the form of a Fish, then of Tortoise. Thereafter, He incarnated as a Boar, Man-lion, Parashurama, Dasharatha's son Rama, Krishna, the son of Vasudeva, and then the Buddha. The last one would be Kalki) One of the prominent ideologies of the Hindu religion is the belief in the incarnation of God. This is emphatically stated in the Bhagavadgita, where Lord Krishna, has declared to Arjuna:

यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत ।

अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥

परित्राणाय साधूनाम् विनाशाय च दुष्कृताम् ।

धर्म संस्थापनार्थाय संभवामि युगे युगे ॥

This has been regarded by the scholars as the earliest reference to contain expositions of some of the tenets of the Ekantaka-school. This passage from the Bhagavadgita explains the ideology underlying the Avataravada in the Hindu thought in the clearest possible manner. It does not specify the number of Divine Incarnations, for the god ‘Creates himself age after age, as the condition of the universe demands. The same idea is reflected in the Markandeya Purana, wherein, the goddess declares emphatically:

इत्थं यदा यदा बाधा दानवोत्था भविष्यति ।

तदा तदावतीयहिं करिष्यामि अरिसंक्षकम् ॥

The texts further specify three distinct types of incarnations viz.: avatara, avesha and amsha; of these an avatara is taken to be a complete incarnation; a partial incarnation, more or less of a temporary nature, is known as avesha. The incarnation of a portion of the power of a divine being is characterized as amshavatara. Out of the various incarnations of Vishnu, Rama and Krishna are termed as avataras.

Jamadagni Parashurama appeared in the world for the specific purpose of subduing the Kshatriyas who had, at that point of time become highly arrogant. The God-appointed mission of Parashurama was only to subdue them. After the completion of his work, he disappeared from the universe after surrendering all his powers to Rama - the son of Dasharatha. The Puranas believe him to be one of the eight Chiranjivis of the country:

माकण्डे बढिव्यासो हनुमन्तश्च विभीषण: ।

परशुराम: कृपो द्रौणी सर्वे ते चिरंजीविना: ॥

After confronting Rama, Parashurama, surrendered all his divine powers to the former and retired to mountain Mahendra. Thus the divine powers were with Parashurama only for a short duration, after which he had to part with them, even though he continued to live on earth. The incarnation of Parashurama therefore comes under the category of avesha, or temporary possession, because he retained the divine powers, only for short duration. The texts further state that Vishnu deputed his ayudhas – Shankha and chakra to be born in the world enjoying some of his divine powers; when these emblems are born on earth they become saints and achieve the purpose of their earthly Incarnation.

The most commonly accepted incarnations of Vishnu are ten in number, which are declared to have been assumed by him in ten different ages with the purpose of destroying the asuras. Usually the Lord incarnated for slaying of asuras, but not so in the first two avataras in these there was no destruction of the asuras. In the first the purpose was to save the barque of Manu from deluge as Matsyavatara and in the second to serve as base for Mandarachala in Kurmavatara, wherein he assumed the form of a tortoise and functioned as a pivot for the churning rod when the milk Sean was churned by the gods and the asuras both, using the snake Vasuki as the churning rope, to obtain amrita.

About the early references to the incarnations of Vishnu, it may be pointed out that the Shatapatha Brahmana states that Prajapati took to the form of tortoise; similarly the Taittiriya Aranyaka mentions that the earth was raised from the waters by a black boar with a hundred hands. All the incarnations are more or less directly referred to in later Sanskrit works, like the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and other Puranic texts.

The Matsya Purana (47.39) testifies to the Varaha being first incarnation of Vishnu, who fought with the asuras:

तेषां दायनिमित्तं ते संग्रामास्तु सुदारुणा: ।

वराह्मद्यादशद्वौचशण्डामर्कान्तरि स्वृता: ॥

(There were twelve hard fought battles between the Devas and the asuras for gaining possession of their heritage, beginning from Varaha incarnation and ending with Shanda and Marka).

This Purana further spells out the incarnations on the occasion of each war. The first was that of a Man-Lion (Nrisimha), the second was Vamana, third was that of Varaha, the fourth incarnation was on the occasion of the churning of the ocean, for obtaining the nectar, the fifth took place at Tarakamaya war, the sixth was called Adivaka war, the seventh was Tripura war, the eighth was Andhaka war; the war of the destruction of Vritrasura was the ninth, the Dhatri was the tenth, the Halahala war was the eleventh and the twelfth was the terrific war named Kolahala. (. Matsya Purana, 47.40-43).

The above passages of the Matsya Purana do not deal strictly with the Chronology of the Avataras, but rather spell out the prominent wars fought by the Devas with the asuras.

According to Dr. J.N. Banerjee the term avatara is applied to the act of die god coming down in the form of a man or an animal on the earth and living there in that form till the purpose for which he had descended on earth was accomplished. It also sometimes denotes the assumption of different forms by the god for the attainment of a particular object. It is thus distinct from the identification (where one deity is identified with the other), or emanation.

One of the earliest references to the assumption of some forms by the divinity for the attainment of specific ends is found in the Shatapatha Brahmana and Taittiriya Samhita where Prajapati is said to have assumed the forms of Fish (Matsya), Tortoise (Kurma) and Boar (Varaha) on different occasions for the furtherance of creation and the well-being of the created. When the doctrine of incarnation in its association with Vasudeva-Vishnu-Narayana was well established, all the three were bodily transferred to that composite god, and were regarded as some of his celestial incarnations.

The Narayana section of the Mahabharata (XII. 349-37) refers in one list to the Varaha, the Vamana and the Nrisimha incarnations. The human incarnations refer, no doubt, to Vasudeva-Krishna, Bhargava Rama and Dasharathi Rama in Chapter 389 (verses 77-90) of the same section, besides the stories about the first three in the list are also given, in addition to the human incarnations stated above.

But a fuller list of the incarnations is given in verse 104 of the same chapter which contains the names of Hamsa, Kurma, Matsya, Varaha, Nrisimha, Vamana, Bhargava Rama, Dasharathi Rama, Satvata, Vasudeva or Baladeva and Kalkin.

Though the number of ten incarnations here is right, the name of the Buddha is not mentioned. Could it be that the Buddha had not incarnated at that point of time, when this section of the Mahabharata was compiled?

In Chapter 98, verses 71ff of the Matsya Purana the number of ten incarnations mentioned include, Yajna, Nrisimha, Vamana, Dattatreya, one unnamed in the Tretayuga, Jamadagnya Rama, Dasharathi Rama, Vedavyasa, Vasudeva Krishna and Kalkin. Buddha is also absent here. Besides Matsya, Kurma avataras are replaced by Yajna, Dattatreya and Vedavyasa.

The Bhagavata Purana (Ch. XI-4, 3ff) provides a list of the avataras thus:

Purusha, Varaha, Narada, Nara-Narayana, Kapila, Dattatreya, Yajna, Rishabha, Prithu, Matsya, Kurma, Dhanvantari, Mohini, Narasimha, Vamana, Bhargava Rama, Vedavyasa, Dasharathi Rama, Balarama, Krishna, Buddha and Kalkin.

The Varaha, Agni and Matsya Puranas count the number of incarnations as ten:

मत्यस: कूर्मो वराहश्च नरसिंहोउथ वामन: ।

रामो रामश्च ऋृशश्च बुद्ध कल्कि च ते दशः ॥

Matsya Purana 4.2

Thus it would be evident from the above that in spite of some difference in the number of incarnations, in the texts the most accepted are the ten incarnations which are defined by the Matsya and the other Puranas.

Besides the Varaha incarnation has been conceived both in the animal as well as the composite forms in the ancient texts.

The Smritis mention both the forms namely; there is morphic or Yajnavaraha and anthropomorphic or Nrivaraha. Vridha Harita describes Varaha as of large body, large neck and prominent tusks shining like a mountain of silver and bearing hundred eyes and hands, lifting Prithvi with his tusk, he embraces her with his hands:

बृहत्तनु बृहदूग्रीव॑ बृहददृष्टमू ।

राजताद्रि समप्रख्यं शतबाहु शतेक्षणम् ॥ बुद्ध हारित (3.333-34)

The Varaha form of Vishnu is also eulogized in the texts with the following epithets:

(i) Ekashringa (Mahabharata 13.149.70)

(ii) Mahashringa (Mahabharata 3.142.45)

(iii) Nrivaraha

(iv) Adivaraha

(v) Bhuvaraha.

(vi) Yajnavaraha

(vii) Pralayavaraha.

In the above epithets Varaha has been termed as Ekashringa and Mahashringa. U.P. Shah (JOIB) V. 1. VIII-1959, pp. 41-70) has contested Ekashringa to be a boar. On the basis of a passage from the Rigveda, he feels that "It is certainly not a description of a boar, wild pig or an ordinary pig. It is the rhinoceros that signifies the Mahabharata description of Varaha, since the skin on its body looks uneven due to thick folds and from mouth to the tail the surface of the body of the rhinoceros seems to have three elevations. Again it is the rhinoceros that can be really described as Ekashringa and not the boar or the pig (Sukara)".

The idea of Ekashringa appears to have been derived from the legend of Matsya, because in the Mahabharata (III. 185) Prajapati in the form of a mythical fish has been called Shringin and its having one horn only is specially mentioned. An earlier version of the same story is found in the Shatapatha Brahmana (1.8.1.5) which specifies only one horn for the mythical fish.

समल्य उपन्यापुष्ठवे तस्थ शूझ्षे पाशं प्रतिमुमोच तेनैतमुत्तरं गिरिमतिदुद्राव ।

Like the one horn of Matsya, the expression of Ekashringa points only to the mythical and supernatural character of Varaha.

New Delhi.

10th October, 1992

Shanti Lai Nagar

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is deeply indebted to the Archaeological Survey of India, the Mathura Museum and other sources, that were kind enough to supply the requisite photographs, which have illustrated this work.

My grateful thanks are also due to Dr. H.N. Singh, of the Archaeological Survey of India, who has been kind enough not only to provide me the necessary help in the composition of the work, but has taken pains to even go through the texts. I am also indebted to Smt. Poornima Roy for helping me in tracing e references for the work and also for composing the Bibliography. I am beholden to Aryan Books International for bringing this book in an excellent manner.

New Delhi.

10th October, 1992

Shanti Lai Nagar

CONTENTS

1. Preface

2. Acknowledgements

I. Introductory.

II. The Episode and its Salient Features:

i) The Bear,

ii) The Deep and Vast Ocean or the Deluge,

iii) The Earth,

iv) Hiranyaksha.

III. Literary Sources:

Rigveda, Atharvaveda, Shatapatha Brahmana, Taittiriya Brahmana, Taittiriya Aranyaka, Taittiriya Samhita, Chhandogya Upanishad, Kaushitaki Upanishad, Mahanarayani Upanishad, Mukti Upanishad, Varaha Upanishad; Ramayana, Mahabharata; The Puranas: Agni, Bhagavata, Brahma, Brahmanda, Devi Bhagavata, Harivamsha, Kurma, Matsya, Padma, Shiva, Vayu, Vishnu and Vishnudharmottara; Parashara Samhita, Aparajitarehchha; Tamil Sangham Literature.

IV. The Epithets: Adi or Bhuvaraha, Yajnavaraha, Pralayavaraha.

V. Iconography:

i) Varaha, Adivaraha, Bhuvaraha, Nrivaraha,

ii) Yajnavaraha,

iii) Pralayavaraha,

iv) Mahavaraha,

v) Varaha in Boar Form.

VI. The Plastic Art.

VII. The Epigraphs, Seals and Sealings.

VIII. Other Aspects:

i) Varaha as all gods

ii) Varaha as Bhrigu and Angirasa

iii) Varaha as Emusha,

iv) Varaha as Ghrita Kumbha

v) Va-aha as Prajapati,

vi) Varaha as Prishajya,

vii) Varaha as Rudra or Manyu,

viii) Varaha as Saheja Agni,

ix) Varaha as Satya and Dharma,

x) Varaha as Surya,

xi) Varaha as Trayi Vidya,

xii) Varaha as Uchchhishtha,

xiii) Varaha as measure or’ currency.

IX. Shiva and the Boar.

X. The Vaikuntha Form.

XI. The Boar in Buddhism.

XII. The Boar in Jainism.

XIII. Varaha Temples.

XIV. Varahi.

XV. Epilogue.

I

INTRODUCTORY

रसाज्ञतामवनिमचिन्तविक्रमः सुरोत्तमः प्रवरवराहरूपधृक् ।

वृषा कपिः प्रसममथैकदंष्ट्रया समुद्धरद्धणिम तुल्यपौरुष: ॥

Matsya Purana 148.79

(The Lord Vrishakapi, of unequalled valour and prowess, has thus brought deliverance to the Earth in most excellent Boar-form, by means of his single tusk).

Historical Overtones

The theme behind the Varaha episode as told in the ancient Sanskrit literature, be it the Vedas, the Puranas or other texts; is the rescue of the earth from deluge or from the bondage of the demon Hiranyaksha. Of these the concept of deluge is of considerable antiquity, while that of Hiranyaksha was introduced during sufficiently later period. When considering the actual causes for the development of this episode, one has to peep into the political and other social conditions prevailing in the ancient past. Though it would not be possible to examine the entire evidence available in this regard, but it would suffice to restrict the discussion to the period starting from a few centuries before the Christian Era.

It is on record that since the days of Cyrus (558-553 B.C.) parts of India to the west of Sindhu and some parts of the Punjab, were frequently invaded by foreigners and also had to undergo the trauma of foreign rule — the Achaemanian empire. During Mahapadma’s time in 326 B.C. Alexander, the Macedonian, with his thundering legions, entered North-west India, the erstwhile satrapy of Iranian empire. In a few months, however, he retreated from India. His occupation of Indian territory was short lived and he could neither face the might of the Nanda empire nor leave any lasting impression on the people. The Indians fought him heroically yielding to him for some time. Soon after the departure of Alexander from the Indian scene, the mighty Mauryan ruler Chandragupta drove the Greeks from Punjab in a brilliant war of liberation. The successful war against the Greeks awoke Chandragupta (324-300 B.C.) to a consciousness of his strength. Chandragupta and his teacher the Brahmana Chanakya, are credited with waging a successful war of liberation; a vast empire unifying India, politically as well as administratively. Hindu Dharma was re-established by organising the life on which was founded the invulnerable culture-consciousness of Indians in succeeding ages. Inspired by his teacher Chanakya, Chandragupta marched to Pataliputra, after consolidating his position in the Punjab, killed Dhana Nanda and assumed sovereignty of Magadha. He further vanquished Selucus, the Greek, who was moving towards India to recapture Alexander’s lost possessions, and later Started on a career of becoming possibly the first architect of an all India empire. Thus for the first time the writ of one emperor ran in the country through an hierarchy of centrally appointed officers.

This concept of throwing away the foreign domination of the country by the native rulers, was amply projected in the episode of the rescue of the earth by the boar form of Vishnu. This was to some extent projected in the sculptural art as well, when we refer to the sculpture from Bhita, dating back to the 2nd century B.C. which has been discussed in some detail in the chapter on “the Vaikuntha form” in this work. This specimen stands to testify that the boar form of Vishnu was getting popular with the people as early as the Second century B.C. possibly in the background of the foreigners’ invading Indian territory and its liberation by Indian forces.

Asoka (273-236 B.C), the grandson of Chandragupta, styled as (दिवानां प्रिय) “the beloved of the gods” and (प्रेयदर्शी) “of lovable appearance succeeded to the throne of Pataliputra by winning a fratricidal war. Nine years after his accession he rounded off the empire which he inherited from his grandfather, by annexing Kalinga. He has to his credit the period in which India, made gigantic advancement in building, cultural and other activities which made his name immortal in the history of India. During his rule, Buddhism flourished and many stupas and monasteries were established, besides sending the Buddhist teachers to the foreign lands. But the welfare States, which eschew armed coercion of the recalcitrant elements, are not known to Survive. As soon as Asoka died, his Buddhistic bearings and pacific policy evoked open resistance. Due to the lack of a vigorous military policy, the outlying provinces rose in revolt. The Greeks again invaded India and advanced into the country up to Ayodhya and Chitoor. Further disintegration was halted only when Pushyamitra (187-151 B.C.) the Brahmana minister of Sunga dynasty took over, what was left of the empire of Asoka—the Great.

The Sunga period was succeeded by Kushanas who overthrew the Sunga rulers. It is to this period that the Bhita sculpture of Vaikuntha, with a figure of Varaha belongs. In the subsequent period of the Kushana the theme of the rescue of the earth gained further popularity. An image of Varaha of the late Kushana period (3rd century A.D.) housed in the Mathura Museum has been reported in the Indian Archaeology — A Review, 1964-65, (PI. LVII-C). In this sculpture the goddess earth has been shown as lifted by Varaha. She is seated over the left shoulder of the god. This testifies that the theme of rescue of the earth by Varaha form of Vishnu had gained sufficient following by the 3rd century A.D. besides developing the iconographical features of Varaha. So appealing was the episode of the rescue of the earth by Varaha that several Puranas patronised it, with various type of descriptions. It is during this period possibly (3rd-4th century A.D.) that the Varaha Purana was compiled, which tells the Varaha story in its Chapter 248. The subsequent Puranas possibly adopted the same story with slight variations here and there.

The Kushanas were overthrown by the imperial Guptas, whose powerful king Chandragupta Vikramaditya forcefully exterminated the vestiges of the foreign rule and extended the limits of his empire to the ocean (Bay of Bengal) on the east and the sea (Arabian Sea) in the west by the conquest of the Vanga and Aparanta respectively. Not only that he launched a gigantic programme of consolidating his empire extending his empire to the north-west up to Bactria on river Oxus, and by entering into an alliance with the kings of the South. A glimpse of this is available in the Raghuvamsha (Chapter 7) of Kalidasa. The writer of Varaha Purana observed the political intimations with their inspiring exposition of the Mahavaraha conception on a philosophical plane which met with the natural approval.

During the post-Gupta period the country was subjected to numerous foreign invasions and each time a native ruler overthrew the foreign domination, it was taken to mean as if the earth was liberated by Varaha. This accounts for the use of Varaha by various monarchs like Chalukyas and others as their royal insignia and even the embossing of their coins with the figure of Varaha.

Genesis and Evolution

In order to discuss the presence of Varaha-the Boar form of Vishnu in Indian art and literature, it would be quite pertinent to have a view of the etymology of the word Varaha (वराह). According to V.S. Agrawala, the word ‘Varaha’ may be split up into two parts Vara and aha providing the etymology as: वृणोति इति वरः The significance is to refer to the principle of force, which envelopes, prescribes a limit to an unlimited or unbounded field and thus by controlling potency gives form to that which was formless and brings forth a system of forces and counterforces, regulated or balanced according to the magnetic rhythm. Now this System is best illustrated in Surya and its Solar system and therefore the main Varaha form is exemplified in Surya. (The relationship of Varaha with Surya has been discussed elsewhere in this work but here we are mainly concerned with the etymology of Varaha-the Boar incarnation of Vishnu.

Varaha-the third incarnation of Vishnu has been popular in the Brahmanical panther from the remote past. It is not possible to give any specific date from which Varaha — the boar became popular in ancient India and when he penetrated into the religious or sacred annals. This would be evidences from the fact that in the Rigveda (1.6.1.7 and 8.77.10) mention is made of a myth in which Vishnu is said to have carried away a hundred buffalos and cooked rice milk which were guarded by Emusha — the boar. This boar has been regarded as a fugitive designation of Vritra. In the same text a casual reference to Rudra as the boar of the sky (1.114.5) could lead one to believe that there existed an Indian counterpart of the German Wodan with the boar. Yet this animal in some way or the other is also associated with Brahmanaspati, Soma and other gods in the Rigveda. (9.97.7 and 10.67.7).

In the Atharvaveda (12.1.48) there is a short reference to an association between Varaha and the Earth. It forms part of the important hymn to the earth which, here, as well as in the later times, is represented as being ever-burdened by the follies of mankind, In the Shatapatha Brahmana (14.1.,2.1 1) Emusha is said to have rescued the earth from the deep water. The Taittiriya Aranyaka (1.10.8) testifies that the earth was lifted by a black boar, with a hundred arms. In Taittiriya Brahmana it is Prajapati, assuming the form of a boar who plunged into the waters and finding the earth down below, lying in the deep waters he raised it. On it, Prajapati, becoming Wind, moved, he saw the earth, becoming a boar he took it up; becoming Vishvakarman, he Wiped the water from it, when he rubbed it; it was extended.

Indeed in the Taittiriya Samhita and the Brahmanas, the creator, Prajapati subsequently known as Brahma, took to the form of a boar for the purpose of raising the Earth out of boundless waters. The Samhita says, “This universe was formerly waters, fluid. On it, Prajapati became wind and moved. He saw this Earth. Becoming a boar, he took her up. Becoming Vishvakarma, he wiped (the moisture from) her. She extended. She became the extended one (Prithvi). From this the earth derives her name”, “the Extended one”. “The Brahmana is in accord as to the illimitable waters and adds”, Prajapati practised arduous devotion (saying). “How shall this universe be developed?” He held a lotus leaf standing. He thought, ‘There is somewhat on which this lotus rests. He as a boar having assumed that form-plunged beneath it. He found the earth down below. Breaking off (a portion of her), he rose to the surface. He then extended it on the lotus leaf. In as much as he extended it on the lotus leaf. In as much as he extended it, that is the extension of the extended one (the earth). He became (abhut). From this the earth derives her name of ‘Bhumi’. The Shatapatha states, “She (the Earth) was only so large, of the size of a span. A boar called Emusha raised her up. Her Lord Prajapati, in consequence prospers him with this pair and makes him complete”.

In course of time, the boar, which took pity on Earth became identified with Vishnu. In the Mahabharata (3.142.28 ff) it is stated that the population of earth, the support of all beings and the producer of all sorts of grain, increased to such an extent that the planet sank down under the weight. Then Vishnu assuming the form of a boar lifted her up from the nether regions into which she had sunk.

Dr. Muir gives two accounts of this incarnation from two recensions of the Ramayana. In one, which he considered as the older one it is said that Brahma assumed the form of a boar, in the other, Vishnu in the form of Brahma is said to have accomplished this work. The alteration of the text is quite noticeable.

“All was water only, in which the earth was formed. Thence arose Brahma, who was self-existent with the deities. He then becoming a boar, raised up the earth, and created the whole world with the saints his sons.” In the later one it is said that, "All was water only through which the earth was formed. Thence arose Brahma, the self existent, the imperishable Vishnu. He then becoming a boar, raised up this earth and created the whole world”.

In the following account from the Vishnu Purana, it will be noticed that, as in the last quotation from the Ramayana, it was Vishnu in the form of Brahma who became a Boar. As the earlier writers had declared this to have been Brahma’s work, it was necessary to identify Vishnu with him.

“Tell me how at the commencement of the present age, Narayana, who is named Brahma, created all existing things. At the close of the last age, the divine Brahma, endowed with the quality of goodness, awoke from the night of sleep, and beheld the universal void. He, the supreme Narayana … invested with the form of Brahma … concluding that within the waters lay the earth, and being desirous to raise it up, created another form for that purpose. And as in the preceding ages he had assumed the shape of a fish, or a tortoise, so in this he took the form of a Boar. Having adopted a form composed of the sacrifices of the Vedas for the preservation of the whole earth, the eternal supreme and universal soul plunged into the ocean.” In a note on this passage in the Vishnu Purana by Professor Wilson, it is stated that, according to the Vayu Purana, the form of the Boar was chosen because it is an animal delighting in water; but in other Puranas, as in the Vishnu, it is said to be a type of the ritual of the Vedas, for which reason the elevation of the earth on the tusks of the Boar is regarded as an allegorical presentation of the extrication of the world from a deluge of sin, by the rites of the religion.

The earth, it is said on seeing the god bowed with devout adoration and addressed the boar as he approached in a hymn of great beauty, in which she reminded him, that she was dependent on him, as in fact are A things. Being thus praised, “The auspicious supporter of the world emitted a slow murmuring sound like the chanting of the Samaveda; and the mighty Boar, whose eyes were like the lotus, whose body was vast as the Nila mountains, and of the dark colour of the lotus leaves, uplifted upon his vast tusks the earth from the lowest regions. As he reared up his head, the waters that rushed from his brow purified the great gages, Sanandana and others residing in the sphere of saints. Through the indentations made by his hoofs, the waters rushed into the lower world with thundering noise. Before his breath, the denizens of the Janakaloka were scattered, and Munis sought for shelter amongst the bristles upon the body of the Boar, trembling as he rose up supporting the earth, and dripping with water. Then the great sages Sanandana and the rest, residing continually in the sphere of saints were filled with delight, and bowing lowly, they praised the stem eyed upholder of the earth."

Commenting on the physical features of the divine animal, the Vayu Purana says, “The boar was ten yojana in breadth, and a thousand yojana in height, his colour was like dark cloud and his roar was like a thunder. His bulk was vast like a mountain; his tusks were white, Sharp and dreadful; fire flashed from his eyes like lightning and he was radiant like the sun. His shoulders were round, fat and large; he strode along like a powerful lion; his haunches were fat, his loins slender, and his body smooth and beautiful.” The Matsya Purana describes the Boar similarly. The Bhagavata, however, describes the Boar, “as issuing from the nostrils of Brahma. He was, at first of the size of a thumb, and then increased to the height of an elephant”. This text further adds a legend of the slaying of Hiranyaksha who in a former birth, was a doorkeeper at the palace of Vishnu. He refused admission to a number of sages, who had come for an audiences with the god. This refusal so enraged them that they cursed him; in consequence of which he was reborn as a son of Diti. When the earth was sunk in the waters, Vishnu was seen by this demon in the act of raising it. Hiranyaksha claimed the earth, and defying Vishnu, they fought and the demon was slain.

According to V.S. Agrawala, the theme of Varaha is closely associated with the history of the country more so during the Gupta period. He feels that Chandragupta Vikramaditya was one of the great Gupta rulers, who annihilating the vestiges of foreign rule also extended the limits of his empire up to the ocean (महोदधि) on the east, the sea on the west by his conquest of Vanga and Aparanta respectively. His gigantic programme of acquiring territory (धरणिबन्ध) included direct conquest of north-west up to Balhika or Bactria on the Oxus (cf. तीर्व्वा सप्तमुखानि एवं समरे सिन्धोर्जिता बाह्निका:) and a system of peaceful alliance with kings of south (referred to as प्रस्तापन by Kalidasa in Raghuvanisa.7), i.e., restoration of their autonomy or suvereignty, which had been disturbed by Samadrugupta and by this his fame perfumed the waters of the south sea (यस्याद्याप्यधिवास्यते जलविधि वीयिपदक्षिण: Mehrauli Pillar Inscription of Chandra).

The writer of the Matsya Purana is said to have followed the political intimations with their inspiring exposition of Mahavaraha. This conception was on a philosophical plane, which met with national approval. The representation of Varaha and Bhudevi is also found in the Chalukyan art at Badami and in the Pallava art in the Varaha Mandapa at Mahabalipuram. This political imagery was repeated five hundred years later and applied to Gurjara Pratihara King Bhoja (A.D. 936-885) who issued his Adivaraha silver coins in large numbers bearing a replica of the Udaigiri figure on one side and “श्रीमदादिवराह” on the other.

The orthodox explanation of the symbolism underlying the Boar incarnation of Vishnu is given in the Padma Purana. The Vayu Purana, reproduces the same passage word by word. In them it is stated that the sacrifice (Yajna) is as a whole symbolized by the boar and that its various limbs represent the limbs of the sacrifice. The grunt of the boar corresponds to the Sama-ghosa, (the sacrificial part); the tongue stands for Agni (the sacrificial fire) and the bristles constitute darbha-grass, the head is the Brahmana priest, the bowels form the udgatri priest and the genital organ constitutes the Hotri priest required to officiate in sacrifice. The two eyes of the boar are said to be emblematic of day and night, and the ornaments in its ears are taken to represent the Vedangas. The mucous flow from its nose is the ghee which is delivered into the fire by the spoon (Sruva) consisting of the snout (tunda). Prayashchitta is represented by the Varaha’s hoofs and his knees stand for the pashu. The air breathed is the antaratmana, the bones of the boar constitute the mantras, and its blood is the soma juice: The Vedi (the altar) is symbolized by the shoulders of the boar and the havis is the neck. What is called havya-kavya is represented by the rapid movements of the boar; the dakshina fee paid to the priest is the boar’s heart. The wife of the sacrificer is the shadow, while the whole body of the animal is taken as representing the sacrificial chamber. One of the ornaments on the body of the boar is made to represent the ceremony called pravargya.

This symbolism has been duly projected in the Brahma and other Puranic texts as well. The asura of the Golden Eye is said to have stolen the earth and to have concealed it under the Primeval waters. This refers to the incipient stage in which Pranic manifestation had not become effective, although it existed in principio. It is the Principle of Varaha which conquers the asura and bringing the Golden Eye in his Power, gives an initial Push to the creative process. Prithvi or Bhudevi represents mother-hood not only of our limited world but of the whole creation. She is the Yoni or Womb, namely primordial Prakriti or Pradhana in which the self-existent Creator, Svayambhu deposits his germ, This womb was seized by the asura, but even he had the eye of gold namely Hiranya or Prana, which finally becomes the Sprouting germ opening on to the conscious world. In the Puranas, Hiranyaksha and Hiranya-Kashipu are two asura brothers, of whom Vishnu incarnated as Varaha and Nrisimha whose birth and exploits are usually narrated one after another, Hiranyaksha is the Symbol of creation ab initio, in the Stage of Prana and Hiranya-Kashipu of the same ab extra on the plane of Prakriti (Matter) which becomes the Kashipu or the golden cushion of life or conscious.

V.S. Agrawala believes that the Vedic Conception of creative modality comprises the five-fold pattern of Svayambhu, Paramesthi, Surya, Chandra and Prithvi; the first two being unmanifest and the last three manifest. They are known as Pancha-Pura, Panchajana, Panchakristhi, Panchadeva or the pentadic scheme of creation. Each one of these has its Varaha or the enveloping principle by which its respective forms are held fast together round a fixed centre which does not permit the force to disintegrate and the forms to disrupt. These are together known as Panchavaraha which are detailed as follows:-

(i) Svayambhu as Adivaraha

(ii) Paramesthi as Yajnavaraha

(iii) Surya as Shvetavaraha

(iv) Chandra as Brahmavaraha

(v) Prithvi as Emushavaraha

All these are the same as the five Pranas according to the same scholar, which are the essential life-principles manifest in Matter. Thus the Pancha-Varahaki principle is not different from what is known as Pancha-Kosha and Pancha-Prana which are the support or mainstay of the Panchabhutas.

Besides the symbolical and Philosophical aspects, the Puranas point to the sanctity to the episode of the rescue of the earth by Varaha, They testify to the actual place on which the Varaha emerged with earth. The Varaha Purana (Ch. 140.4) describes it to be a sacred Place just where Koka emerged. This seems to be the location of Kokamukhasvamin. In fact the actual name of Kokamukha appears in the same Purana. In Chapter 122, verses 19-22. The Varaha form of Vishnu testifies to the rescue of Prithvi from the deep ocean, As to the place where the Varaha form of Vishnu first appeared, it may be pointed out that the same text (140.24) testifies Vishnusaras as the place where Varaha pulled out the earth with the stroke of the tusk. Cunningham believes Varaha-Kshetra in Basti district of Uttar Pradesh as the place where Varaha appeared with the earth.

The texts further believe (Enthoven, R.E., The Folklores of Bombay, Oxford 1924, p.83) that on the third day of the bright half of the month of Chaitra (March-April), Vishnu-Varaha, saved the earth from deep waters, which is an occasion of earth-worship.

Varaha form of Vishnu, has also been known with the following epithets:-

(i) Ekashringa (Mahabharata, 13.149.70). Since the Varaha had a single tusk, he was called Ekashringa.

(ii) Mahashringa (Mahabharata, 3.142.45). The one having a huge tusk.

(iii) Nrivaraha — The one who has the composite form of a man and a boar.

(iv) Adivaraha — The one who appeared to rescue the Earth from primeval waters.

(v) Bhuvaraha — The one who rescued the Earth from deep sea waters.

(vi) Yajnavaraha — The real meaning of the Varaha conception as applied to Yajna is its significance as a symbol of Vedic cosmogony. (The aspect has been discussed in considerable detail, elsewhere in this work.)

It is not in India alone that the boar has been held in high esteem from time immemorial; it enjoyed an exalted position in other countries as well. This aspect has been duly illustrated in the second chapter in this work. But the sanctity or the reverence he enjoyed in India is almost unprecedented. He was considered to be an incarnation of Vishnu who was responsible for the rescue of the Earth-goddess from the deep sea waters after defeating the demon Hiranyaksha. This was apparently the reason why a number of rulers in India, adopted him as their royal emblem. Hemadri eulogised him thus:

सर्पभोगश्व यस्मिनभुजे धरां देवी तत्र शड्डरो भवेत् ।

अन्ये तस्य करा: कार्या पद्म चक्र गदाधरा ॥

II

THE EPISODE AND ITS SALIENT FEATURES

द्रष्ट्ाग्रोदधूता गौरुदधि परिवृता पर्वतैर्निम्न गाभिः ।

साक॑ मृत्रिण्डवत् प्राग्बूहदुरुवपुषाइनन्त रूपेण येन ॥

सो5यं कंसासुरारिर्मुरनरक दशास्यान्त कृत्सर्व संस्थः ।

कृष्णो विष्णु: सुरेशो नदतु मम रिपु नादि देवों बराहः ॥

(Long back, Varaha having a colossal body, rescued with his horns, the Earth-goddess, with all the streams, rivers, mountains, who was surrounded by the waters of the sea, like a small clay ball. He, who is the enemy of Kamsa, Mura, Naraka, Ravana; is omnipresent and is also known as Suresha, Krishna and Vishnu, may protect us).

In the entire episode of the rescue of the Earth-goddess from the deep sea waters by the boar form of Vishnu, as available in the Puranas and other classical literature the followings are its essential parts, viz.:

(i) The Boar

(ii) The Deluge

(iii) The Earth

(iv) Hiranyaksha.

These elements, though of completely independent nature have been so interwoven in the story, that one looses its significance without the other. Though the account available in the Sanskrit texts about the entire episode of the rescue of the Earth-goddess from the deep sea waters has been discussed in considerable detail elsewhere in this work, but here it is intended to discuss about these elements with global ramifications.

(i) The Boar

Before entering into a discussion of the myth relating to the rescue of the earth from the deep seas by the god, it may be useful to ascertain the role played by boars and pigs in popular belief, in other parts of the world. Boar represents indeed the male of the domestic pig, guinea pig and various other mammals; or both sexes of wild hog species belonging to the family of Suidae. The European wild boar, referred to as Sus-scrofa, is the largest of the wild pigs, distributed over Europe, North Africa, and central and northern Asia. -It has a coat of pale grey to black and prominent tusks. The animal is long extinct in British Isles and north-west Europe, but is still found in marshy woodland districts of Spain, Austria, Russia and Germany. The boar is one of the four heraldic beasts of the chase and was the distinguishing mark of Richard III, king of England.

From earliest times, because of its great strength, speed and ferocity, the wild boar has been one of the favourite beasts of the chase. In some parts of Europe and India it is still hunted with spears and dogs, but the spear has mostly been replaced by the gun. It is found throughout India, Myanmar (Burma) and Sri Lanka.

At the outset it may be pointed out that generally speaking pigs are somewhat different from boars. While the former are referred to as tame and domesticated animals mainly meant for human consumption, the latter are wild animals, full of strength. The boar can therefore justly claim to be one of the bravest wild animals and one of the best armed, having a tusk over its snout. The wild boar has not only been frequently referred to in ancient Indian art and literature, but in the folklores of the peoples’ of the central and northern Europe. The grunting hogs and boars which root out the grub in the earth were very often believed to represent storm or thunder clouds, cyclones, etc. Their tusks were identified with lightning. In the Mahabharata (3.272.54) the grunting or roaring of the boar is Compared to the Sound of thunder, when Vishnu is stated to have taken to the form of a boar roaring like thunder and being as black Clouds. With the Cells and the Germans, the boars were apt to be regarded in a Sinister light and might well be the embodiment of demonic beings hunting and walking about. [1] They are supposed to know about the weather and to have fore-knowledge of it. Often parts of their bodies are used in popular medicines, love spells, or in the magic intended to promote fertility. These animals are, indeed, almost generally held to concern themselves with fertility and agriculture. This inter alia appears from the widespread belief that the boar or a sow is the animal embodiment of the spirit of com. In Germany and other countries bounded by the Baltic, the last of the harvest is called the Rye-boar; it gives occasion for songs praying for plenty of food and other good things. The com spirit in the form of a pig - which is believed to have a fertilizing power; plays his part also in sowing rites: as a pig he is put in the ground at the sowing time. In the custom connected with the Scandinavian yule boar the com spirit, immanent in the last sheaf, is held to appear at mid-winter in the form of a boar made from the corn of the sheaf; part of it is given to the ploughman and his cattle to eat, in the conviction that it will exert a quickening influence on crops. These animals were often symbolical of Wachstumkraft to such a degree that solemn vows intended to promote luck and fortune were made over their heads, that the god of agriculture Freyr and his sister Freyfa had their special boars, [2] and they were thought to be closely connected with the goddess of clouds whose task it was to fecundate the earth. In the Celtic world to the boars were connected with the spirits of the earth. [3]

Although in ancient Greece the boar was sacrificed on various occasions, it was especially sacred to Demeter and Dionysus who again were concerned with agriculture. In the mysteries of these deities, pigs were regularly sacrificed. [4] The Greeks were also acquainted with the custom of swearing by the pig. An interesting ceremony called the ‘Eidopfer’ is described by Homer (11.19.250 ff); a wild boar is slaughtered as an offering to Zeus, the Earth, the Sun and the Erinys (the avengers of perjury). At the moment when Pluto carried off Persephone a swineherd chanced to be herding his swine on the spot, and his herd was engulfed in the chasm down which the god had vanished with the young goddess. In commemoration of this fact young pigs were annually, at the Thesmophoria - a women’s festival in honour of Demeter, let down into caverns. Afterwards, the decayed remains of these animals and of cakes and other objects, were fetched by women who descended into the caverns and brought up these remains. He, who got the piece of the decayed flesh and cakes, mixed it with seed-corn kept for sowing. He showed the mixture in his field and believed that he would surely have a good crop. [5] The objects thrown into the pits together with the pigs were imitations of male sexual organ made of dough, snakes and twigs with pine-cones, all of them being well known ingredients of fertility rites. A hog was, further, remarkably enough, one of the animals which nursed the young Zeus, the god who, in a way typical of deities concerned with vegetation, according to the certain belief, was periodically reborn. [6] According to a Greek legend a Calydonian boar was sent by the goddess Artemis to ravage the gardens and meadows of Anatolia because she had been offended by the King Ocneus. Meleager, the king’s son succeeded in killing the boar; Atlanta Meleager’s beloved, took part in the hunt.

In addition to the above evidence concerning the presence of boar in the religious practices of ancient Greece, there is enough of material depicting its popularity in contemporary art and numismatics.

The use of Electrum money before 500 B.C. in the city of Clazomenac in Greece, is not quite certain, but it may probably claim the specimens bearing a boar’s head, such as starter with four parts of winged boar: rev. quartered incuse square, and perhaps a piece with boar’s head and an archaic inscription; rev. two incuse squares of different sizes. The inscription [7] on the latter may be the name of King Sadyattes of Lydia, although the type is doubtless that of Clazomenae and refers to the terrible winged boar, which according to tradition, once inhabited the district. Copies of gold staters of Philip II of Macedon contained a symbol, forepart of winged boar; and Alexandrine tetradrachms. Another set of coins contained on them, symbols, forepart of winged boar or of a ram’s head. [8]

Silver [9] coins from Cyzicers belonging to 480-400 B.C. depict forepart of boar rev. lion’s head in incuse square. The late retention of the incuse is noteworthy. Silver [10] coins from Lycia belonging to 520-480 B.C. also have a boar on the obverse. Silver coins [11] from Aspendus belonging to the 500-400 B.C. project a nude horseman with a boar on the reverse. The silver coins from Phocis dating back to the 480-371 B.C. sometimes [12] contain a female head, and sometimes the forepart of a boar — an animal sacred to Artemis. The silver pieces [13] from Aetolia belonging to 279-168 B.C. and have the head of Artemis or Atlanta; rev: boar. This design also appears on some bronze coins, while other bronze pieces have male head; rev. trophy or spear-head and boar’s jaw-bone; or, head of Pallas; rev. Herakles.

Crete

An abundance [14] of sculptures is found in Crete which belongs to nearly 2000 B.C. The best works, it is interesting to note are miniatures, ivory seals carved in shape of figures, which were discovered from graves. Examples of these are from a tholos near Plantanos and a boar’s head and a lion killing a man. Wild boar is also found [15] engraved over seals of Aegean period besides other animals.

Rome

The Roman author Varro in discussing harvest and marriage customs, mentions also the sacrificial boar. At harvest time the Roman peasant offered a sow to Tellus, the goddess of earth, and to Ceres, who presided over the growth of crops. The slaughtering of the so-called porca praecidanca, offered to these goddesses conjointly had a dual purpose: it served as an introductory rite to the harvest and also as an expiatory ceremony intended for the deceased who, as is well known maintains close relation with the power of controlling fertility. [16]

A frieze on Trojan’s column in Rome, belonging to A.D. 120 depicts the events of two Dacian Wars, besides the mountains, rivers and forests. In the lonely valleys, the boar is also found depicted moving swiftly [17] in its natural habitat, the forest surroundings.

France

In the Franco-Contabrian rock art, preserved in the primitive rock paintings, the contemporary artist used charcoal and ochre which offered him shades and colours ranging from yellow to brown. In the cave paintings at Altamira besides other wild animals, the wild boar is also depicted. [18]

Egypt

In ancient Egypt pigs and other related animals were impure from the ritual point. Yet a more original attitude towards these animals is still recognizable: once they were regarded as representatives of fortune and associated with the great goddess Isis, or what may have been the preceding stage, with Nut, the sky-goddess who was at the same time a mother deity. [19] Moreover in Egypt the boar was also conceived to be the demon Sat and the “black pig” was the devil in Wales and Scotland and also in a layer of Irish mythology. Hatred for boar prevailed in Egypt and other neighboring countries, and still lingers in parts of Ireland and Wales but specially in the highlands of Scotland. The Gauls, like the Aryans in India, did not regard the boar as a demon. [20]

Spain

In the Stone Age cave art of Spain several animals are found painted on the walls, in which the boar is also Boar-hunt present. A lively scene of a wild boar hunt, painted in dark red comes from Cueva del val del Charco dal Agu Amarga (Spain). In this painting the boar is fleeing fast, followed by a hunter. The hunter has already thrown his spear at the animal, half the length of the spear has penetrated into the body of the boar. The figure of the boar has been drawn quite neatly. [21]

Mesopotamia

Amongst the several hundred stone vessels from Jamdat Nasr cemetery at Ur some are unique; for example the broad rim of an alabaster vase is cut almost to proper thinness so as to take full advantage of its translucence or a great jar of grey diorite is given a shape well-nigh Greek in its perfect proportions. Some of the animal Carvings are excellently executed, which include a couchant wild boar in Steatite, found from Ur which is a fine piece of miniature sculpture. It is indeed a Tare example of a sculpture in the round which belongs to 2800 to 2600 B.C. [22]

Osnea and Australia

It is not that the boar was popular for hunting, religious sacrifices or food purposes in the region, but its bones and tusks were used by the primitive people of the islands of the Pacific Ocean for making ornaments which were worn on special occasions like a community dance or in war. Alfred Buhler 23 has referred to a stylized human figure decorated with mid-ribs of palm-leaves, cordage, univalve shells, feathers and boar’s tusks painted in red. It is held by teeth on a flap tied round the neck with a cord. There is another male figure from Mbranda, middle Yuat, Sepic district, which is painted with earth pigments and decorated with human hair, univalve shells, rings besides boar’s tusks. These were possibly mythological figures which were created to ensure success in warfare and hunting, besides curing of sickness. The boar’s [24] tusks were also used in making face masks as well, as would be evident from the drawing of a mask reported from the lower Sepic [25] area in the Pacific Ocean. In this region, of course, animal motifs could have originated. Often the primeval monsters are visualized as boars, eagles or crocodiles. Boar s tusks were particularly favourite decorations on funerary figures and also served as ornaments. In Crete, [26] the boar’s tusks were also used for decorating the shields of sword blades and helmets of warriors.

Borneo and Indonesia

Although it cannot be claimed that the pig, which is more often than not the cheapest and the most expendable animal, was used as sacrificial offering because it still is, or was, associated with fertility, agriculture, etc., attention may further be drawn to the wide area of occurrence of pig and boar ceremonies, offerings, rites – connected with pregnancy, funeral sowing and reaping, swearing, etc., and of various beliefs regarding pigs in many other parts of the world. In the Island of Borneo, [27] the bridal couple are smeared with the blood of pigs or with a mixture of eggs, water, earth and pig’s blood, for the sake of offsprings prosperity, wealth and fertility. In the Indonesian [28] island of Savu, black pigs are sacrificed to obtain rain and the pink pigs at the time of sowing. The inhabitants of Sandwich Islands sacrifice a pig to allay the evil consequences of a volcanic eruption. [29]

Lithuania

The boar was apparently associated with the fertility cult because of his well known habit of raking up the soil. The wild pig and the boar usually do considerable damage to the crops. As such they have to be conciliated for the sake of successful harvest. In Lithuania, the earth is held to bring forth like a mother; after a period of rest she can be fecundated again, but at sowing time, a festive dinner party is given in which the offering of head and legs of a hog are made obligatory in order to signify the fertility aspect. Perhaps the curious method of sowing and reaping described by Herodot (2, 14) which is rarely met with, may also be mentioned here. After having sowed his land, the Egyptian farmer let hogs into it to disturb the soil and it was expected that the seeds will take deep root. Afterwards, at harvest-time he had the corn trodden out by the same animals. Of greater relevance is the tradition recorded by Grimm. [30] The boar by uprooting the soil taught the art of ploughing toman. This detail of German folklore has its counterparts elsewhere. The furrows were considered as the earth’s belly or female organs. Thus the boar’s uprooting was viewed as similar to ploughing, tilling, fertilising and was considered as a form of generative activity. In Sanskrit the word potra “the snout of a hog” was also used for ploughshare.

India

The different aspects of the boar form of Vishnu appearing from the earliest times in Indian art, literature and Culture, have been discussed elsewhere in the work. The discussion here concentrates on the exclusive treatment of boar/hog in Indian art, literature and folklore.

(i) Literature

Although the ancient Indians have not left us much information on boars and other animals, the facts found in the texts point to their Presence in one form or other. In works dealing with omens and Prognostication hogs and boars are more than once mentioned together with animals and objects which are closely related to water, moisture and fertility and which generally forebode rain. Av Par. (61.1.7) Presence of boars, makaras [i.e. creatures living in water, often confounded with dolphins, crocodiles, etc; (65.1.4.)], aquatic plants, makaras, serpents, crocodiles, alligators, porpoises, conches, trees, tortoise, fresh lotus flowers, reed, etc. together with buffalos are signs of immediate rain when clouds appear (65.2.2); Varaha. BS. (28.14) “clouds resembling in shape waves, hills, crocodiles, tortoise, boars, fishes …… give water within short time”. A boar or hog can, however, also be a bad omen as well [31] and they are supposed to cause wounds, attacks and hostilities. There are other indications of the boar’s supposed connection with powers residing in the fertile soil made of conch-shells, ‘dolphins’, bamboos, elephants, [32] boars, snakes and clouds.

In the Rigveda (1.61.7; 8.77.10) mention is made of a myth in which Vishnu earned away a hundred buffalos and cooked rice-milk which was guarded by, or at least had something to do with a boar, called Emusa, who had apparantly taken up his station on the other side of the mountain. This boar has been regarded as a ‘figurative’ designation of Vritra. The Taittiriya Samhita (6,2,4,2f) relates that once the sacrifice went away from the gods in favour of Vishnu and entered the earth. As Indra declares himself to be “a slayer in an inaccessible place”, Vishnu replies,” I am a carrier off from an inaccessible place”, adding that a boar, “a stealer of precious objects”, keeps the goods of the asuras concealed on the other side of the seven hills, and asking Indra to slay that boar. Indra does so, and asks Vishnu to carry the boar away. (Vishnu), the sacrifice, then carried him off “as a sacrifice for them”. Thus they won the wealth of the asuras. In the Maitrayaniya version (3,8,3; and Katha Samhita 25.2) Vishnu’s name is not mentioned: Vishnu, the sacrifice “was apart from the gods” and, after being found by Indra, asked that god to slay the boar. The main idea of this myth is clear, the demon killer was to slay the representative of the enemy, now called asuras and the sacrifice; Vishnu the divine power concerned with winning what is most vital and essential for gods and men, manages to secure his treasure. The odana or “valuable goods of asuras no doubt embodies the idea of life sustaining food, nourishment, of longivity, and primary substance essential for life. In the Atharvaveda [33] Odana is called amrita.

It is stated in the Atharvaveda [34] that the boar knows the plant (वराह वेदवीरूधम). The same text as well as Kaushitaki Samhita 35 informs us of a ceremony to be performed with a plant order to be victorious in a disputation; the plant, the root of which is to be chewed is addressed thus, “the eagle discovered thee; the hog (shukara) dug thee with his snout”. In another boar myth from the Atharvaveda, [36] the Varaha is said to keep in its possession the “Odana” or grain marked and cooked with milk, the food par excellence. In the Jaiminiya Brahmana [37] the Varaha is described as having arisen from the testicles of the sacrificial horse. In the Rigveda, (1.114.5) Rudra has been claimed to be the boar of the sky.

Turning now to the boar or hog in the Indian folklore, it may be stated that the animal is found present in many of the primitive folktales and it may not be possible to bring out all of them due to obvious reasons. Still some selective instances can be presented here. The Gonds immolate pigs and offer them to their god Busa Deo and Hindus of central India sacrifice them to their deity Bhainsasura or the Buffalo demon for the protection of crops. When the crops are beaten down at night by the wind it is supposed that Bhainsasura has passed over them and trampled them down. In order to ensure rich harvest the Raj Gonds present an offering to the Earth Mother; she is one of the few deities who accepts pigs. The most usual time for the ceremony is when the crop is half grown. [38] The Sama Nagas and other peoples still perform the important ceremony of eating pork in order to promote the growth of crops. If pork is not eaten at the proper moment the grain will not form according to their faith. [39] The Santhals believe the hog to be engaged in ploughing. [40] The Khairas leave the last ear of the crop to their god Ghorea who is a boar. [41]

As to the archaeological evidence concerning the boar, it may be stated that the animal has been found present in many of the pre-historic as well as historic sites in the country. A few examples are given below.

Bhimbetka

Twenty three drawings of boars, which belong to pre-historic period were discovered in rock shelters of Bhimbetka near Bhopal. These include fine figures of mythical boar (three of them with horns). They are executed in eight colours (white-7, orange-1, light ted-5, scarlet-1, dark red-4, burnt amber-3, crimson-1 and emerald green-1) and six Styles. Fifteen figures have transparent colours and eight have opaque.

Mohenjodaro

Models of swine from the site, are Tare but undoubted figure of a pig was discovered from Mohenjodaro, The figure was badly broken but a bit better preserved One is also available. As this animal is not often represented in the art of ancient Indus Valley, it is reasonable to suppose that the wild pig is represented in these two models. As Col. Sewell has pointed out, all the skeletal remains of a pig that have been found at Mohenjodaro - and they are many – are the Indian boar (Sus Cristatus). The boar may have been used as an article of food or hunted for its tusks. It is significant that it is only the jaws and teeth of the animal that are found, which suggests that the latter were especially valued; yet the teeth of the boar were never used for making anything. It may be, then, that the animal was hunted by dogs, as it still is, in Baluchistan. That this sport was also practised in early Elam is proved by an archaic seal from Susa. Possibly the head alone was brought as a trophy of the hunt.

Dhatva

The bones of a boar were discovered from the Excavations at Dhatva (Gujarat) district Surat.

The boar, which emerged in the vedic literature followed by other classical texts, remained in almost continued seclusion till it was conceived to be an incarnation of Vishnu. Once the boar was identified with Vishnu, his popularity gradually increased and the artist too did not lag behind in carving out lively images of the same. As an incarnation of Vishnu, the boar gained importance in the religious annals and his images both in the animal as well as composite forms became popular with the people as well as rulers. Though both the types of the images of the Boar incarnation of Vishnu are available from the earliest times, but the discussion here is concentrated to the animal form only, the other form having been discussed elsewhere in this work.

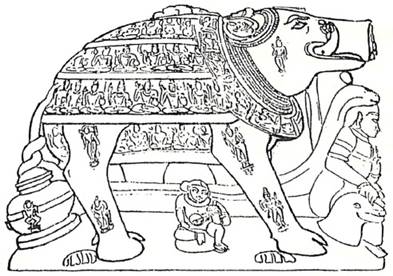

One of the earliest boar incarnations of Vishnu in animal form was discovered from Eran in Madhya Pradesh. Cunningham [42] has described this image thus, “Thus Varaha is interesting for its size and beauty and for being the oldest known Brahmanical statue so far as I call to mind in this part of India, or indeed in all India. I do not mean to imply that more ancient statues do not exist; I mean only that inscribed Brahmanical ones, fixing the age of the statue indisputably have not been found of a date anterior to this. It is very remarkable that the oldest statue should be a Varaha. I should expect if any inscribed statues older than this, of the Vaishnava pantheon be discovered, they would probably be either of fish or tortoise incarnations of Vishnu, for it appears to me that account in Hindu books of various avataras of Vishnu indicates the successive (though not exclusive) forms of images worshipped in Aryan India. It is not here necessary to demonstrate that Vaishnavism in the earlier phases is only a variant of phallic Cult. The primary religion of the Aryans in India as shown in the Vedas was not phallic; they must have therefore adopted it from the races they subdued in India. Phallic worship appears to have existed among them in various forms- they have co-existed with early Vaishnavism”. The Varaha image in boar form at Eran is of colossal size. It measures 15 feet and 6 inches from snout to tail; the height is 10 feet and 10 inches. A garland composed of small human figures sculptured on a band is carved around its neck. The body is not covered by human figures but by small circular ornaments. There is a projection of six inches representing the hump which raises up on the back over the shoulders. The image is bedecked with a Gupta inscription on the under side of the neck. The image is quite interesting from the point of view of its age. [43]

Another image of boar incarnation of Vishnu in animal form, belonging to Gupta period was discovered from the Vishnu temple at Apsad in Bihar. The Earth-goddess is shown here as a female, who has been rescued by the boar from the deep waters. She is holding on to one of the tusks of the boar, who is caressing her with his boar muzzle. The entire body of the Great Boar is covered with miniature figures of gods and sages, lending divinity to the boar figure. The image is executed in grey sandstone in the art of Gupta period. The Varaha-Vishnu stands in front of a huge conical brick mound, truncated at the top, which could contain the ruins of a Vaishnava temple. [44] Similar images were also discovered from Khajuraho, Jhalawar and the other sites.

Two images of boar incarnation in animal form were discovered from Dudhai (Jhansi) and the other which is preserved in the State Museum. [45] Both of them may be dated back to the early medieval period. The image from Dudhai is a Common type of Varaha figure wholly worked out as a boar animal with a thick snout bearing the figure of Earth-goddess in female form on the top. The animal has long tusks and a big body covered with figures of gods and goddesses. The boar image in the State Museum has almost identical features as compared to the Dudhai image. Both of them resemble the similar image found at Eran, as discussed above. Another image of the boar incarnation was discovered from Vijapur in Gujarat.

In the ancient Indian art and literature, there are instances in which the boar decorated the royal banner. There are also instances in which the animal was adopted or patronised by rulers as royal insignia or state emblem.

Varaha, Vihara village, North Gujarat

In the Mahabharata, Jayadratha the King of Sindhudesha has been described as having his flag with an image of Varaha, which also means that Varaha at that point of time was considered to be a sacred animal like Garuda, who adorned the flag of the Pandava hero Arjuna:

स॒वराह ध्वजस्तूर्णगार्ध् पत्रानजिह्गान् ।

आशी विषसमप्ररव्यान्कर्मार परिमार्जितान् ।

मुमोच निशितान्संख्ये सायकान्सव्यसाचिनि ॥

The same trend continued during the historical period when many rulers adopted the boar and extended him the royal patronage and grace, as would be evident from the following illustrations:

Chalukyas

During the historical period some of the rulers placed the boar over their state banners or as royal emblem. The Western Chalukyas used the boar as crest as would appear from the Sanjan grant. According to this grant the boar had the colour of bees, terrible eyes, red at the corners. The invocation of Varaha incarnation of Vishnu at the beginning of many Chalukya grants, no doubt, can be seen in connection with the adoption of the Boar as the royal crest. The Sanjan [46] plates of Buddhavoisa, belonging to the 7th century A.D. invokes the boar form of Vishnu.

Chedis and Kalchuris

The cult of Vishnu [47] was widely popular in the Chedi country, as is evidenced from several inscriptions of the 10th and later centuries. At Banodhogarh and the adjoining Villages of Gopalpur, Goltaka alias Gauda, the amatya of Yuvarajadeva I, caused to be carved out of rocks huge images of several incarnations of Vishnu, including the fish, the tortoise, the Boar, etc. with the following epigraph: [48]

श्री युवराजदेवामात्यस्य श्री भानु सूनो: श्री गोल्लाकस्य

गौड़ापरनाग्न एते गच्छूय (तय) कच्छप सूकराद्यः ।

Similar theme is Tepeated in the Banodhogarh [49] inscription (No.II) of Yuvarajadeva-I.

Further Someshvara, the Brahmana minister of Lakshmanaraja-II, who performed several Vedic sacrifices, erected a lofty and magnificent temple dedicated to the boar incarnation of Vishnu under the name of Somasvamin at Karitalai in Jubalpur district. The remains of the temple are still extent at the place. [50]

Besides the following inscriptions of the Early Chalukyas of Gujarat, also adore the boar incarnation of Vishnu in the Opening verses, since the animal was their royal insignia:

1. Navsari Plates of Yuvaraja [51] Shryashrya-Shiladitya (Kalchuri) year 421.

2. Nasik Plates of Dharashraya – Jayasimha, [52] (Kalchuri) year 436.

3. Surat Plates of Shryashrya – Shiladitya, [53] (Kalchuri) year 443.

4. Navsari Plates of Pulkeshiraja. [54] Kalchuri) year 490.

5. Anjaneri Plates of Bhogashakti, [55] (first set Kalchuri) year 461.

6. Anjaneri Plates of Bhogashakti [56] (second set Kalchuri) year 461.

As many as ten families of Silharas are known to have ruled in Maharashtra and Karnataka according to the epigraphical [57] records though the Silhara dynasties are believed to have ruled, parts of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat from quite early times but the earliest inscription of the Silharas [58] of North Konkan dating back to the 9th Century A.D. was discovered from the Kanheri Caves. The object of the inscription is to record that Vishnu (Gupta) son Of Purnahari made certain grants of money for the worship of Bhagavata (Buddha), for the repairs of a vihara, the clothing of the monks and purchase of religious books. Though Vishnu was another popular deity with the Silharas, but very few references to grants made in his honour are forthcoming. However, there was a temple of Lakshmi-Narayana [59] at Mandavali (district Thana), to which a grant was made m the reign of Keshideva II. It was constructed by Lakshmidhara, a minister of that king. There were some other temples of Vishnu such as that at Brahmapuri near Kolhapur, erected by the Silharas and their ministers. As the Kolhapur Silharas were fervent devotees of Mahalakshmi, the mangala-shloka of many of their charters is in praise of Varaha incarnation of Vishnu, the consort of the goddess. In the Kolhapur Plates of Gandraditya [60] (s.s. 1037) corresponding to A.D.1115, contains a verse in praise of Varaha:

सिद्धम् । स्वस्ति । जयत्याविष्कृतं विष्णोष्वाराहम्

क्षोमिताण्णव॑ (वम्) दक्षिणोन्नत दंष्ट्राग्र विश्रान्त भुवनं वपु: ।

(Success Hail Victorious is Vishnu's manifested boar-form, which agitated the ocean and which had the earth up-lifted resting on the tip of his tusk.)

The said grant further goes on to testify that the Silhara family, which is well-established and is the abode of royal fortune, which has vanquished a number of foes. This could also be interpreted to mean that as the boar incarnation had the sir the Earth-goddess from the vast and deep waters of ocean, so have the Silharas rescued the earth from their enemies.

The same theme has been repeated in following epigraphs from Kohlapur:

1. Kolhapur Plates of Gandraditya, [61] (s.s. 1048) A.D. 1126.

2. Kolhapur stone inscription of Bhoja II, [62] (s.s. 1104) A.D. 1182.

3. Kasali Grant of Bhoja II, [63] (s.s.1113) A.D. 1191.

4. Kutapur Grant of Bhoja II, [64] (s.s.1113) AD. 1191.

Vijayanagar

The rulers of Vijayanagar empire like many other dynasties patronised he boar as their royal emblem, which they inherited from the Chalukyas. “But first we will say a few words regarding such of their coins as have come om to Us. These have been figured in my gleanings, figures 1 to 5 inclusive (Mad. Jour. IV.N.S). Figures 1 and 2 are those already noticed for their similarity to the padmatankas. It needs but a glance to see how exact the imitation has been - and imitation by which they (Vijayanagar rulers) superseded the older and ruder specimens in the Kadamba Section. No.3 copied from Moor’s Hindu Pantheon. pl.104, fig.13, was found in Tipu Sultan’s repository at the taking of Shrirangapatnam. The obverse represents a well formed boar, on the reverse is a floral design only found on older coins. The two are of ruder workmanship and show considerable deterioration from the preceding examples, so much so, that I hesitated whether to assign them rather to the Vijayanagar era. The boar on the coins of the later, of which a considerable number is in copper have been obtained, as also the seals on some of their Shasanams have the addition of a sword in front of or over the back of the animal, and the absence of this characteristic on the two coins above mentioned incline me to leave them among the Chalukya relics. From the extensive circulation of the Chalukya money bearing the figure of this animal, and its adoption by the succeeding dynasty of Vijayanagar, the name of the pieces in most of the vernacular dialects has come to be that of Varaha or boar piece, even when the figure of the animal gave place to that of a deity or some other symbol as happened after the change in the Vijayanagar dynasty from Kuruba to Narasinga line”. [65]

Elliot, furthers [66] testifies in this connection that “The adoption of boar symbol of the Chalukyas by Madhava, with the use of the Nagari alphabet should have appeared more Prominently on the new coinage; but I have Only met with it on the copper money, in which the boar is distinguished from that of the Chalukyas by the addition of a Sword”.

The Udayambakam [67] Grand of Krishnadevaraya of s.s. 1450 is on three copper Plates bored at the top and secured by a ring, attached to which is a seal, bearing Vijayanagara emblem of a boar and the figure of the sun and the moon on the upper half. The grant starts with invocation to the Varaha incarnation of Hari, besides other deities.

Another set of three Copper plates from Kanchipuram [68] of Krishnadevaraya, (s.s. 1444) have also been engraved and bored at the top and secured by a ring. A seal bearing the usual Vijayanagara emblem of the boar, the sun and the moon is attached to the ring. In verse 2 of the epigraph, the boar incarnation of Vishnu has been invoked.

In additions to the above the boar also appeared on various seals and coins, details of which have been furnished in the chapter on Indian art in this work.

(ii) The Deluge

One of the factors which played an important role in the story of the boar incarnation of Vishnu is the deluge in which the earth was submerged in the sea waters. This submerging of the earth into the sea waters necessitated Brahma or Vishnu to take to the form of a celestial boar in order to rescue the earth from the deep sea waters. Interestingly, the stories about the great deluge in which the earth was submerged in deep sea waters, in the ancient past were current in many countries of the world. The physical causes to which the deluge is assigned in different legends are numerous. Naturally enough, it is generally the rains, which caused the flood havoc, drowning everything on earth. In a Sac and Fox North American Indian story, the rain is said to have fallen in drops as large as wigwam. Less frequently it is the incursion of wave, or the pouring in of the waters of the sea on to the land (Makah Indians of Cape Flattery) sometimes it is the sudden melting of winter snow, as when a mouse gnawed through the bag containing the heat and let it out (Chippewas). Sometimes the cause ascribed is quite fantastic. A man accidentally lets fall and breaks the jar containing the waters of the ocean which he had picked up out of curiosity (Haiti), and it is the same motive, with the same fatal consequences, that tempts the ape to remove the mat which covered the waters in a hollow tree through which they communicated with the ocean (Acawaios).

In the Indian tradition the Earth-goddess, more often than not sinks in the deep waters due to the evil deeds of the creatures occupying it; she then approaches the gods, who arrange for her rescue.

In a Finnish story the deluge [69] is of hot waters. According to a legend of the Quiche Indians, a deluge of resin followed one of water, and in some cases fire may be said to take the p ace of water, the conflagration story being in many respects analogous to the more usual deluge of water.

In extent the deluge varies from an obviously focal flood to a universal deluge. Very frequently everything is covered except a few lofty ranges or rocky mountains. In one Australian legend the low island of refuge alone remained uncovered, when the lofty mountain on the main hind, on which the people had taken refuge, was submerged. This idea probably arose from not an uncommon notion that islands float.

A deluge story of the Pelew Islanders [70] is connected with a picturesque account of the origin of the red stripes on the head of the bird called the tarlit. A Persian deluge myth, among other motives, explains the saltness of the sea. In an interesting myth connected with Mangala (Cook Islands), the general purpose of which is to explain the origin of the coconut, the flood is merely required to bring up the eel, out of whom the coconut grew, to the door of the maiden Ina’s hut, whose pious duty it was to slay him.

In the mythological stories current [71] with the American Indians, some animal, a duck or beaver or fish, more often a muck-rat, dives down for earth and brings it up between its feet or in its month. Some have compared the curious sequel to the sending out of birds by Xisuthros in the later Babylonian story. But there the clay on the feet of the birds is a Proof of the re-appearance of ground, on which, though still wet, the birds could walk, and it is a far less poetical variant of the dove and the olive branch. This story preserves some features identical to those available in the Indian accounts of the rescue of the earth in the Varaha form of Vishnu.

The deluge myth of western Australia [72] is connected with a quarrel between the black and white races, and could have originated or taken its present shape only after the first English settlement in the country. In a deluge myth of the Papagos, the Great Spirit, unable otherwise to tame Montezuma’s rebellious tamper, sent an insect into the unknown land to fetch the Spaniards who destroyed Montezuma, an Aztec ruler, who was actually killed by the Spaniards in 1520 and became the demi-god hero of an ancient flood myth.

Some of the deluge stories are explained as part of a definite cosmological System. Some of the deluge myths might certainly be so explained as the Varaha form of Vishnu, rescuing the earth from the deep sea waters. But in such stories the ocean is not so much a deluge as the Primeval deep. As a rule, however, such Conceptions are hardly of a kind to account for the general prevalence [73] of deluge stories.

There are some deluge stories which are explained as nature myths. In this view, some forms of deluge story especially those of Palestine, [74] Babylon, Greece and India are a mythical representation of some natural phenomenon of constant recurrence. Noah in his Ark is generally regarded by its exponents as a sun myth.